This is the work with my undergraduate student Angel Piotrowski. She used her annual volatility data 1928-2023 to replicate my previous work published on arXiv and discussed in my previous blog entry about the new valuation measure for the Standard & Poor 500 and its predecessors. She used the end-of-year S&P 500 close trading price instead of the January S&P 500 daily close averaged price used by me. She used December Consumer Price Index (CPI) data instead of me using January CPI. And she used data only 1928-2023 instead of my work 1871-2023. But this almost a century of data is still enough to make conclusions.

First, adjust earnings for inflation and consider the trailing average of earnings for the last 5 years. This is similar to the classic Campbell-Shiller approach, when the cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio (CAPE) features last 10 years of earnings. But we chose 5 years to make room for more data. Next, take inflation-adjusted wealth

at end of year

Consider the linear regression

This has the meaning of subtracting the trend from relative growth of wealth over earnings. Historical earnings averaged 1-2% per year and wealth growth is around 6-7% per year so the value for the trend must be 4-5%. This equation shows that after detrending, this is the classic autoregression of order 1. We can rewrite this in the more standard ordinary least squares regression form:

where we define for short notation the quantity which we called implied dividend yield:

This gives us and

and

All three coefficients are significantly different from zero: Student T-test gives

values

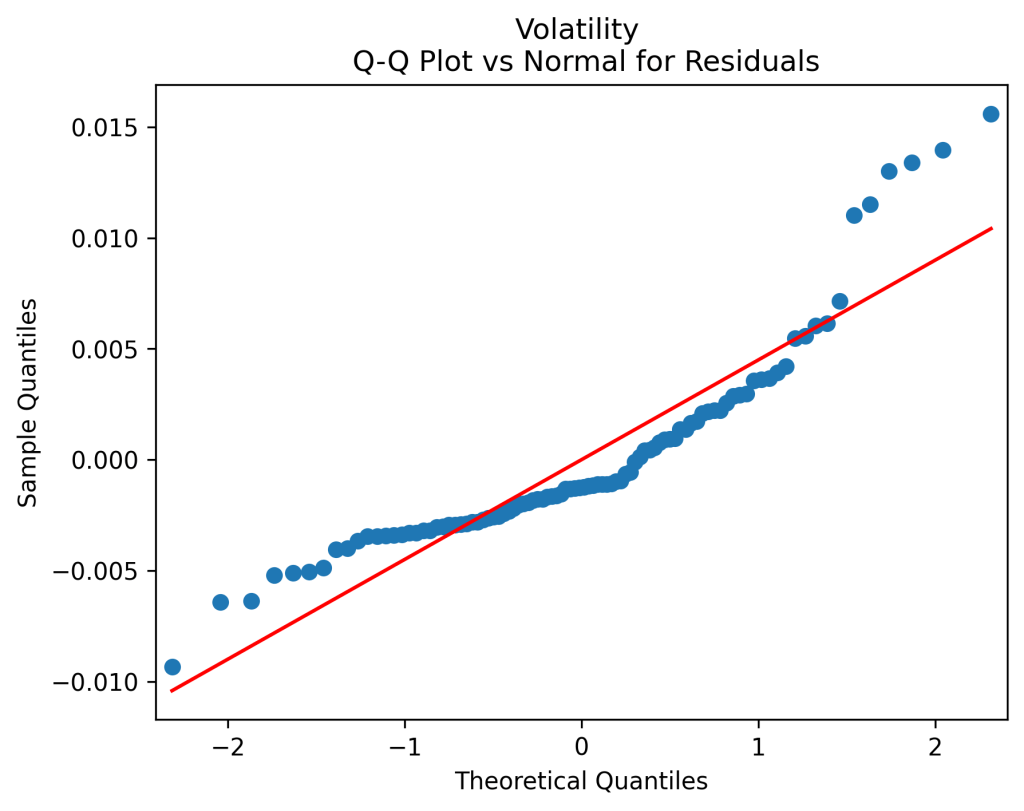

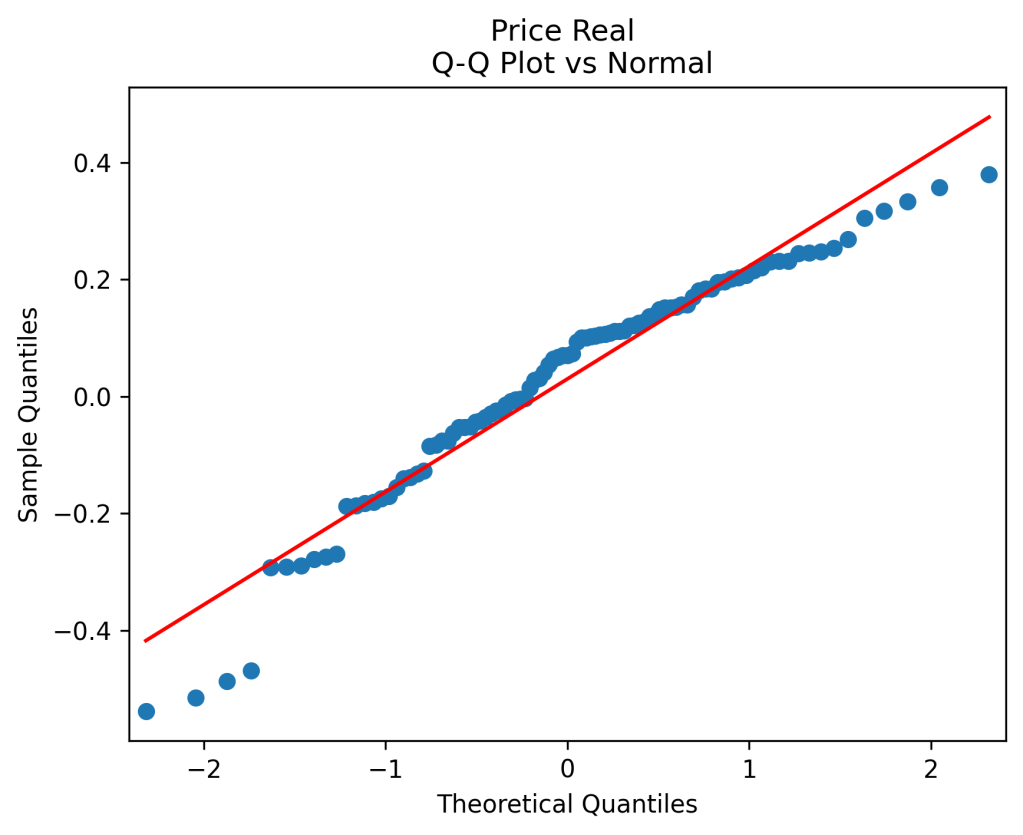

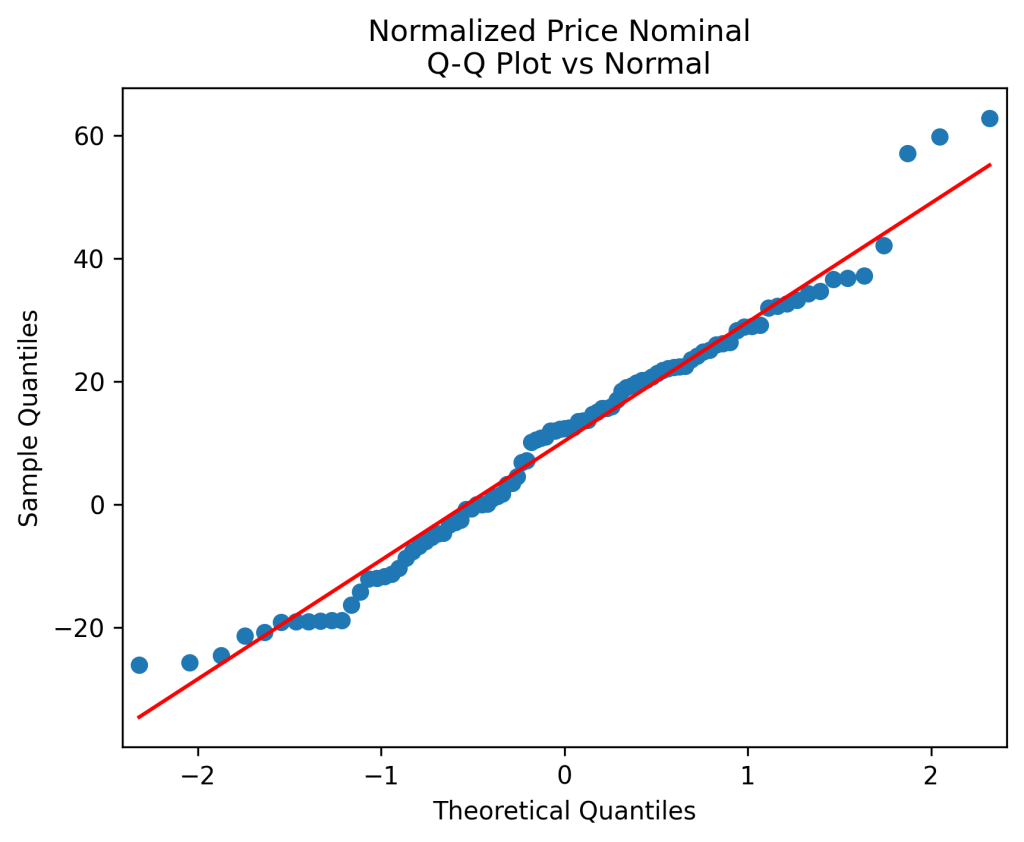

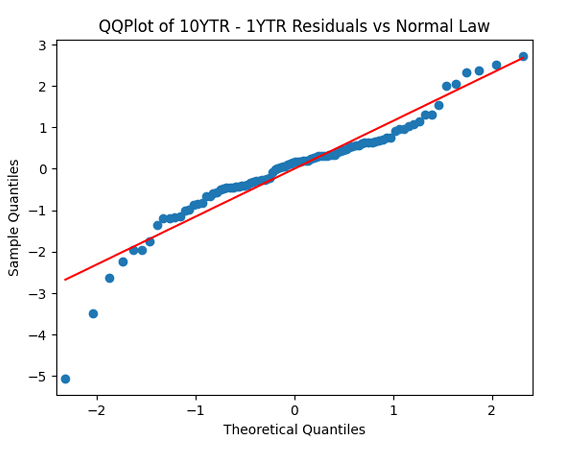

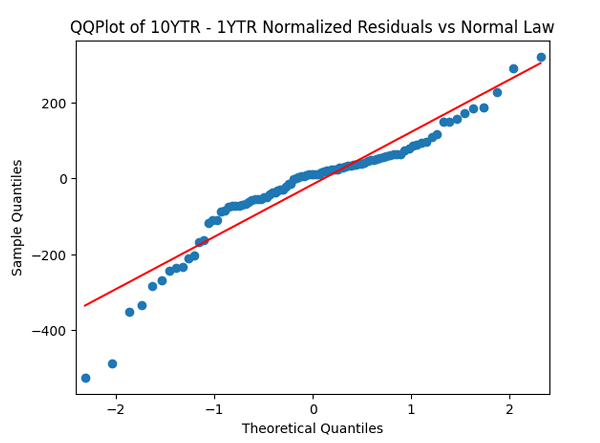

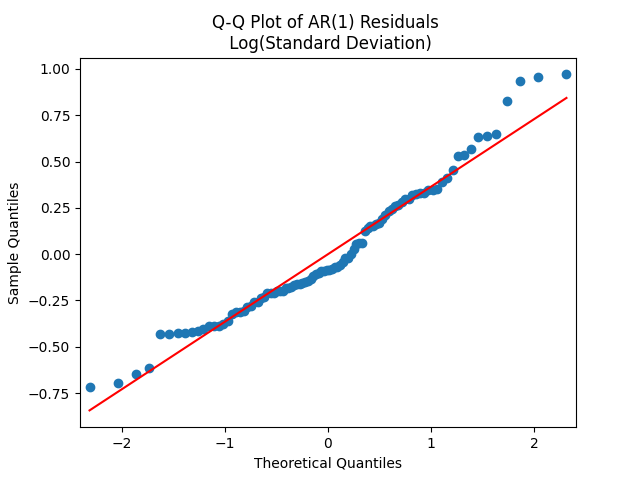

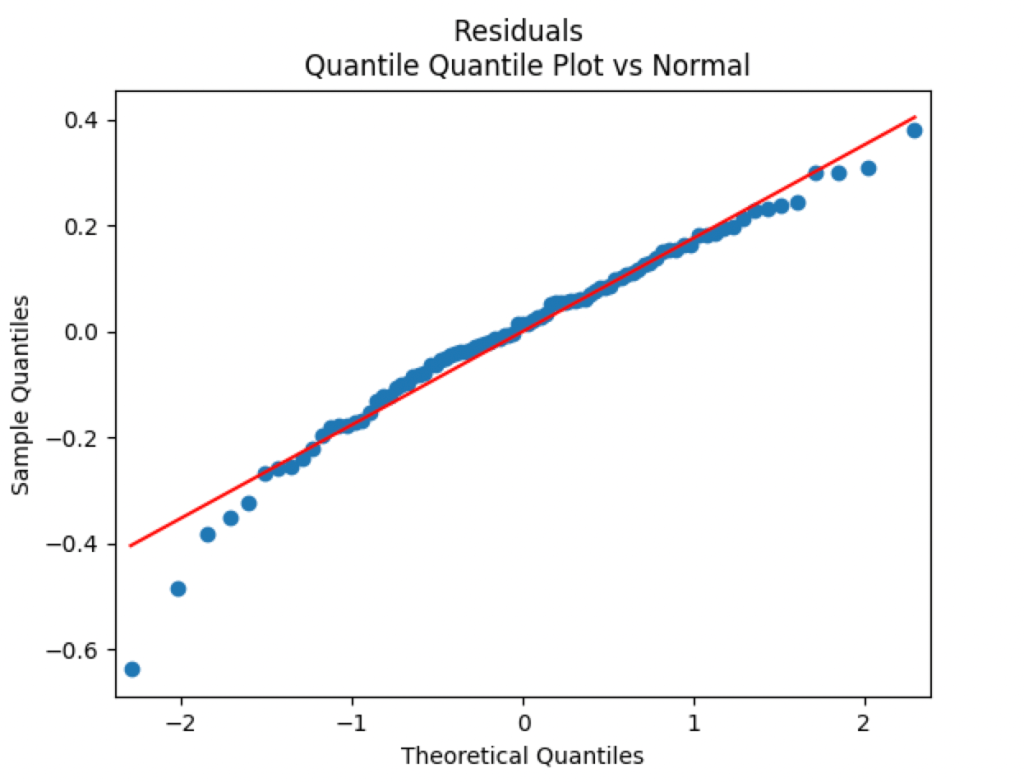

But the Jarque-Bera test shows that innovations are not Gaussian:

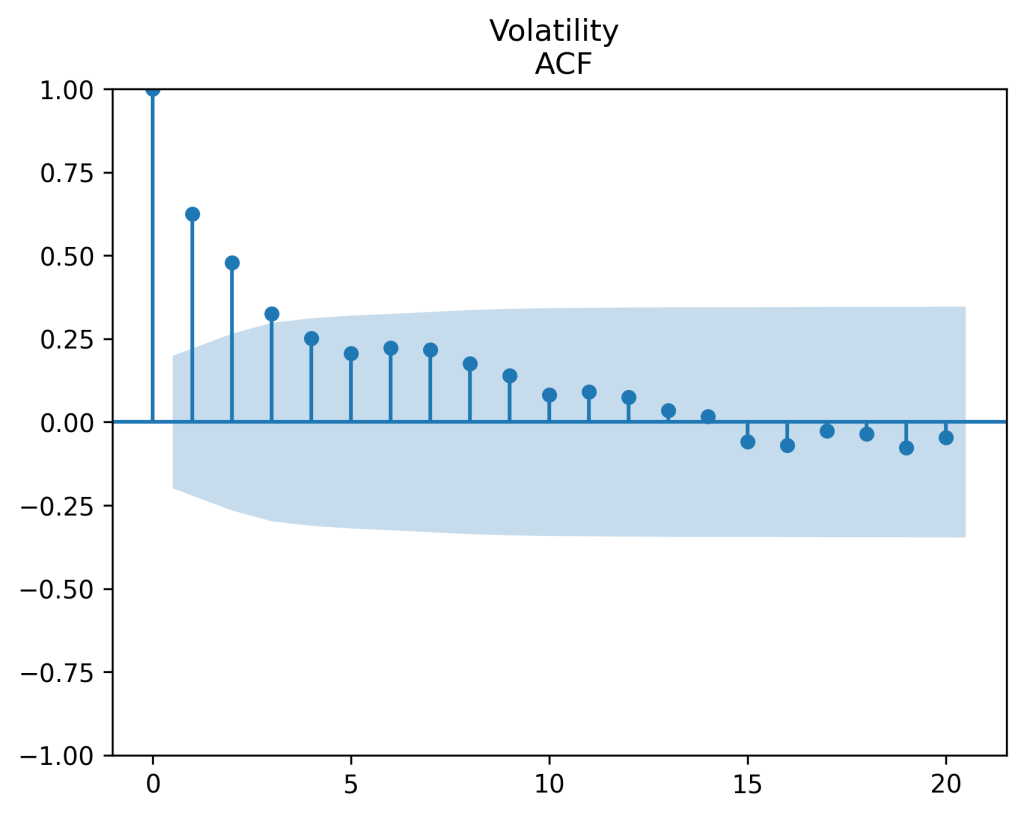

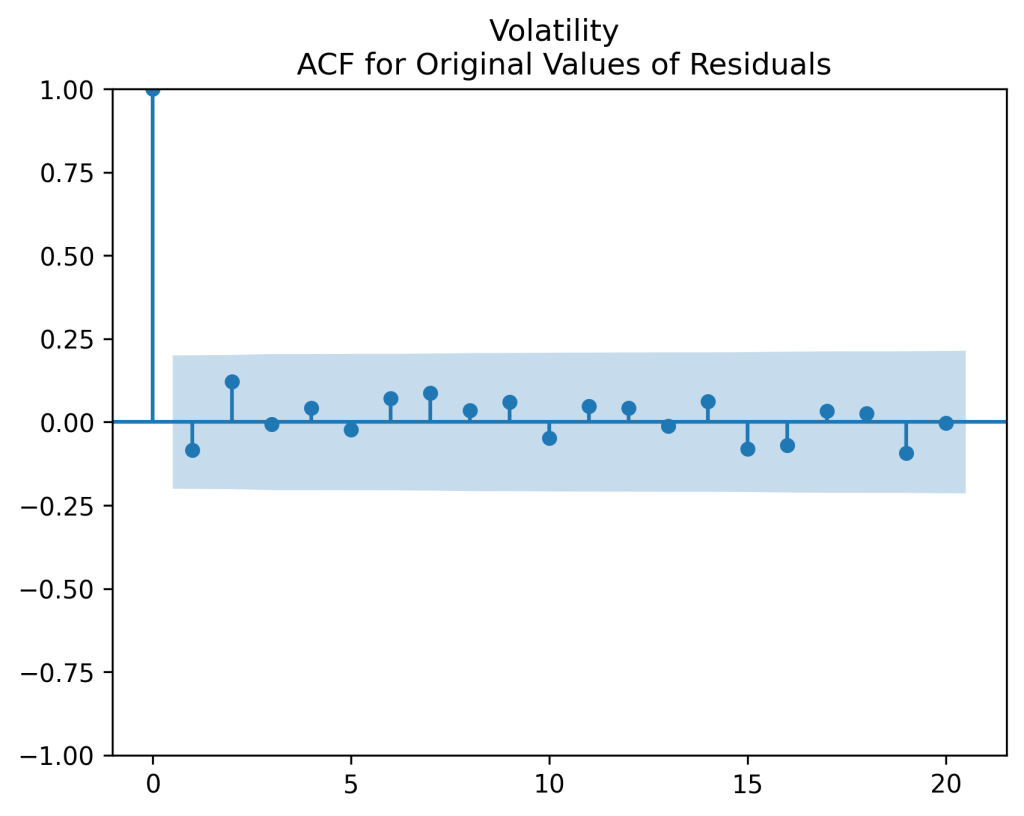

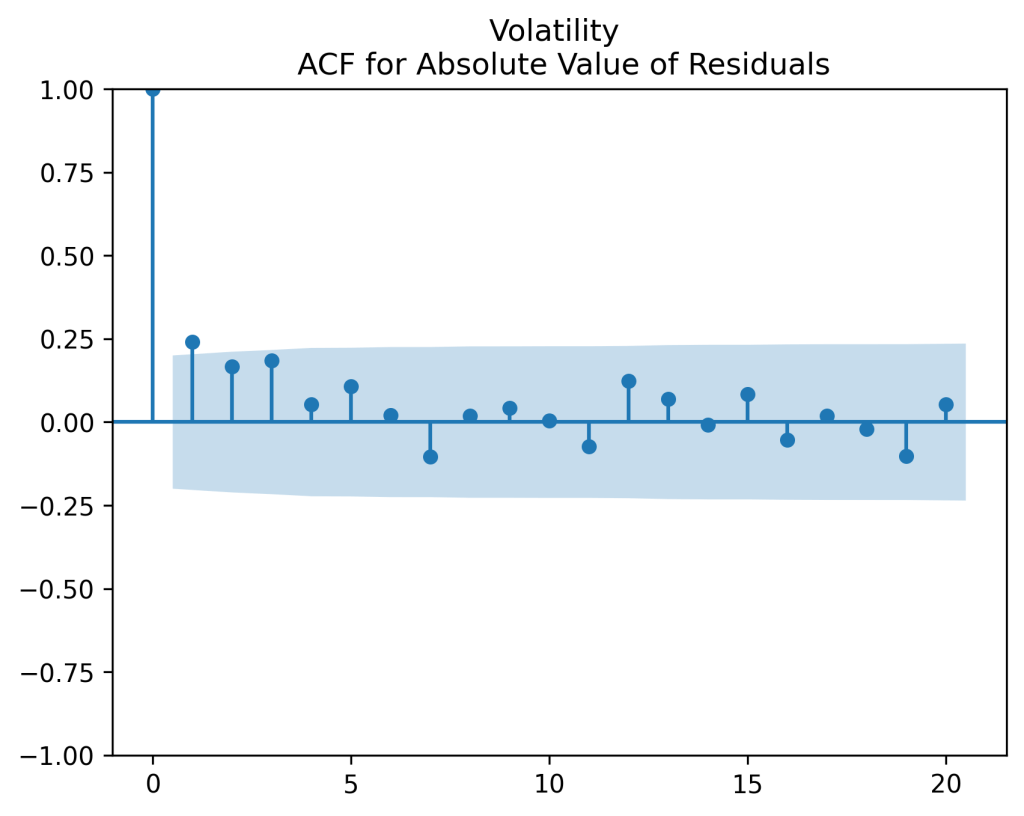

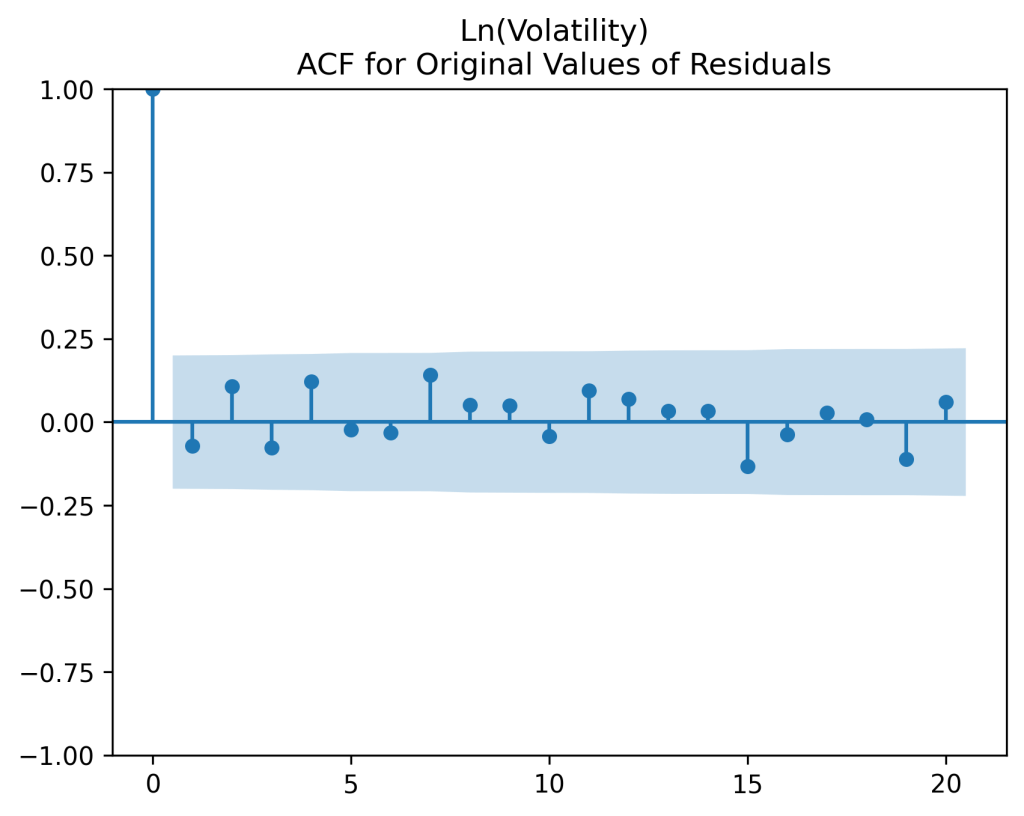

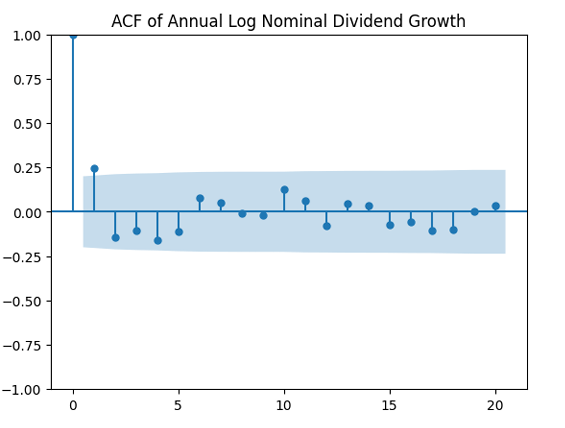

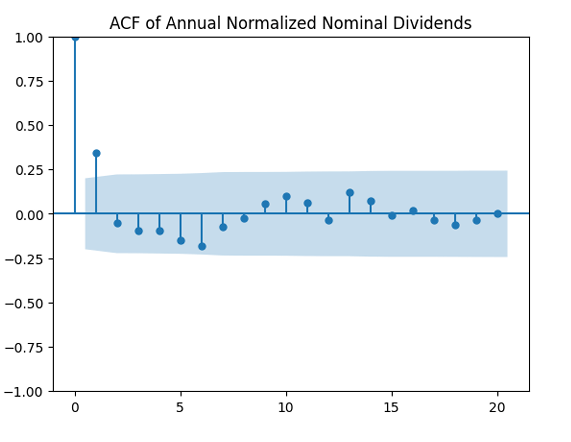

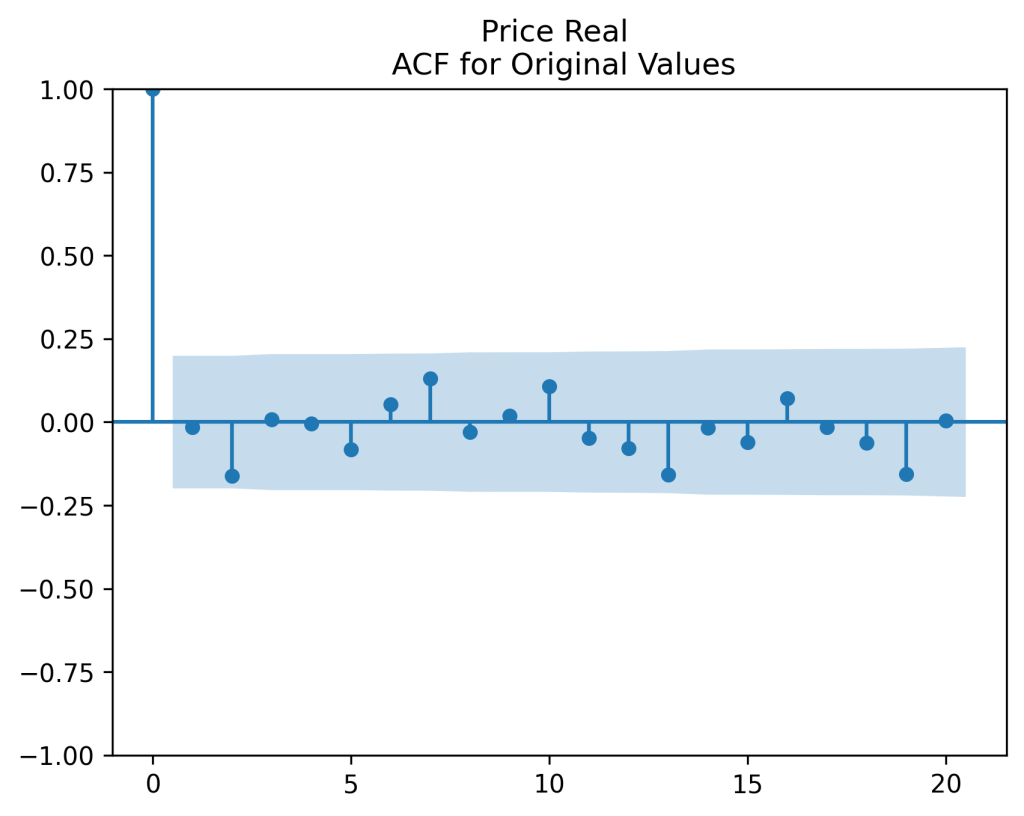

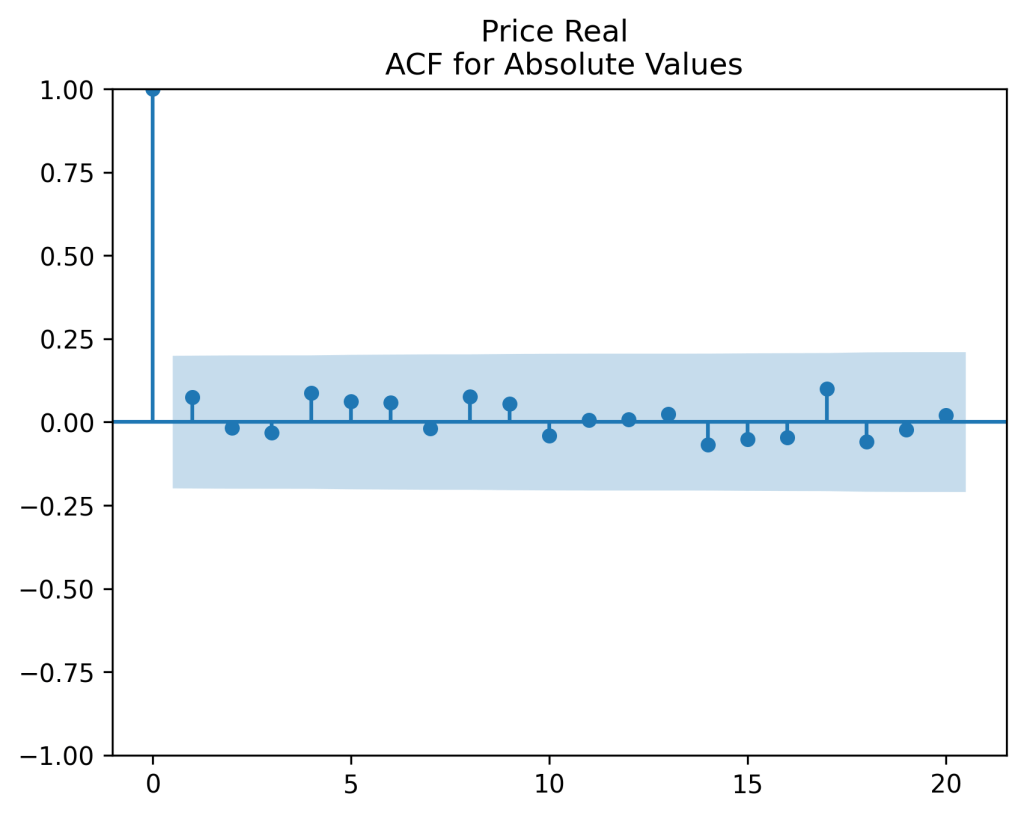

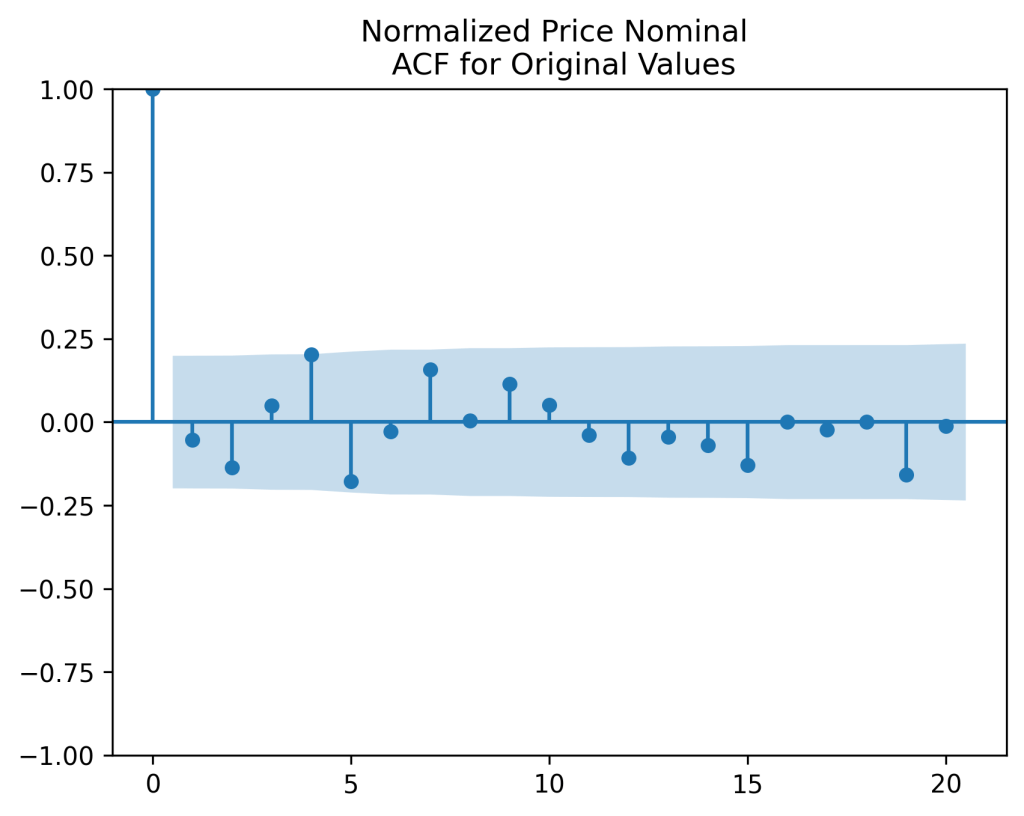

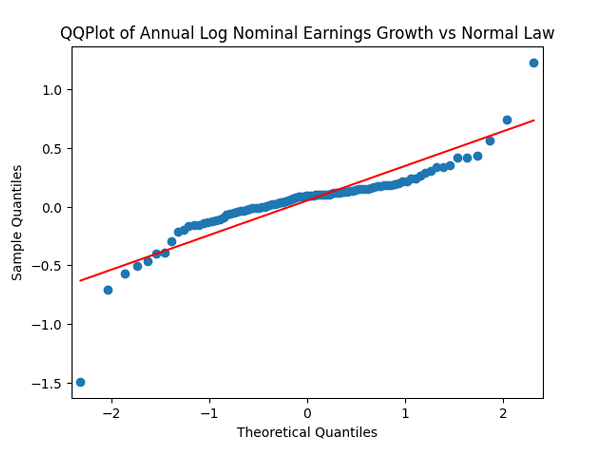

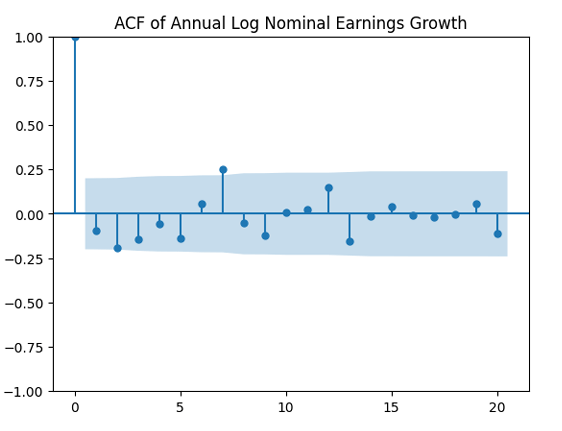

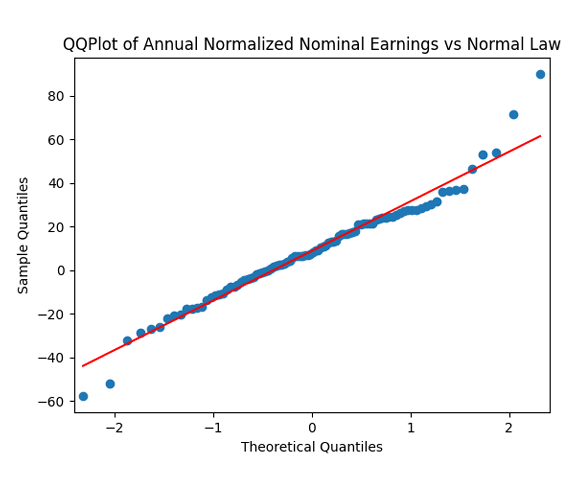

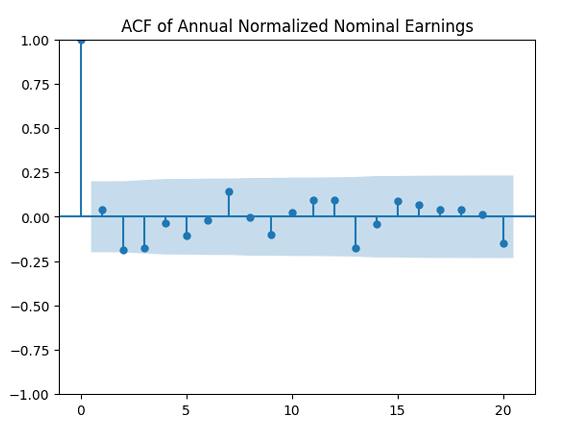

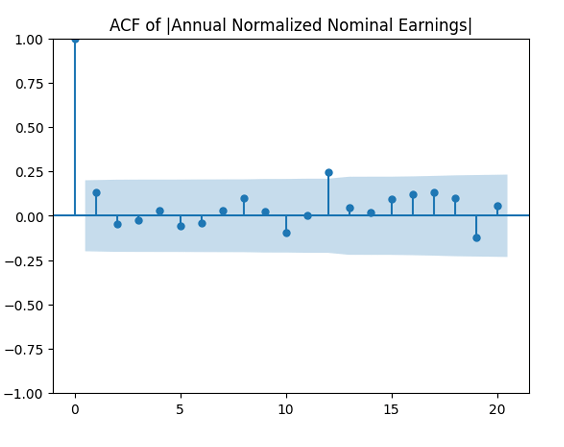

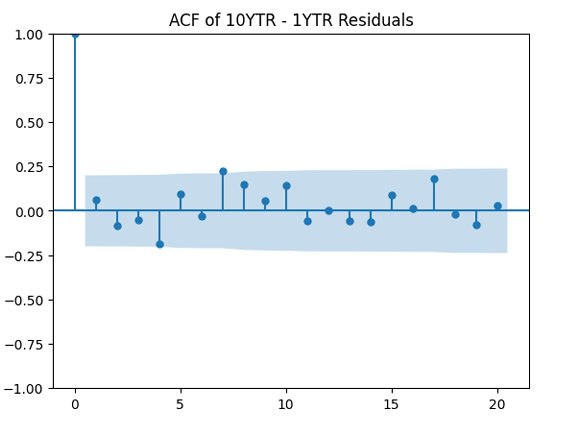

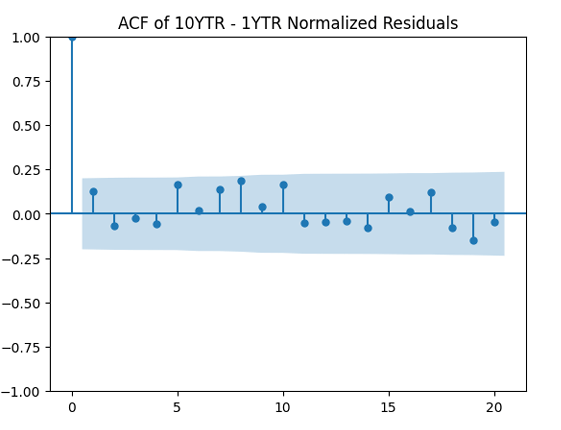

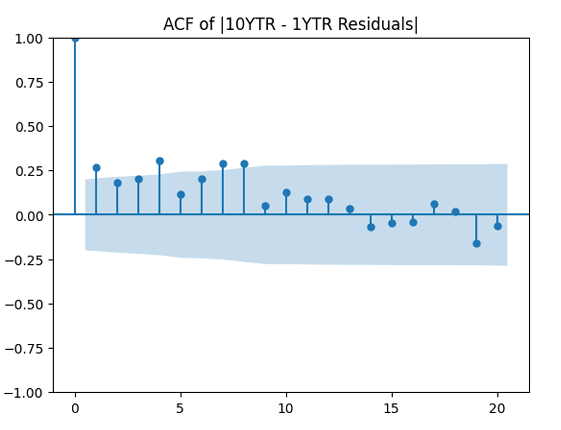

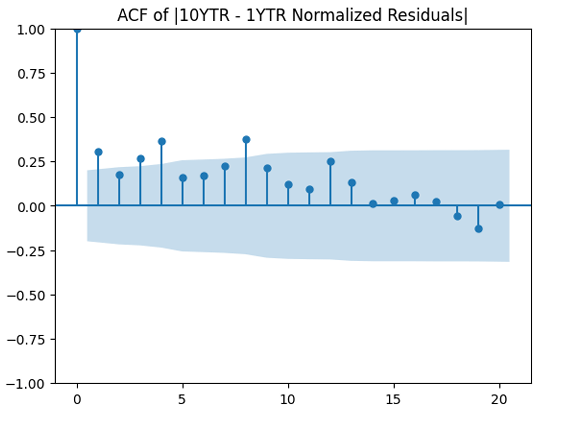

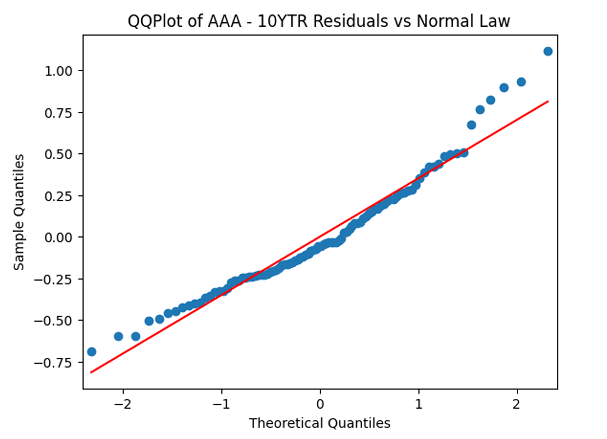

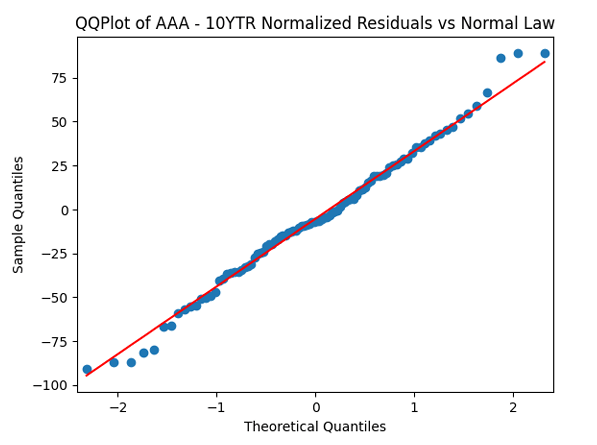

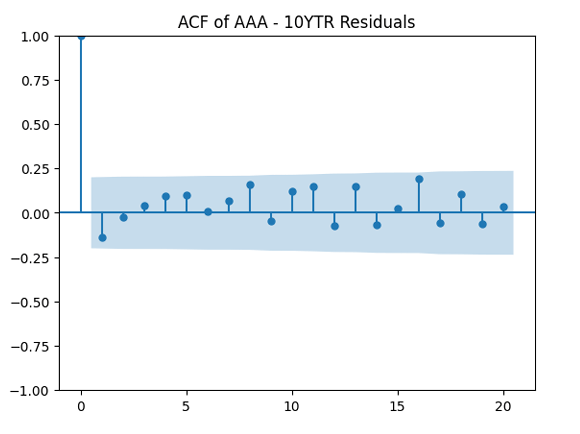

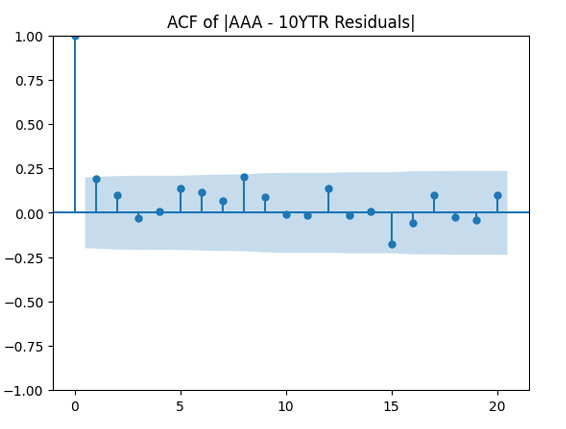

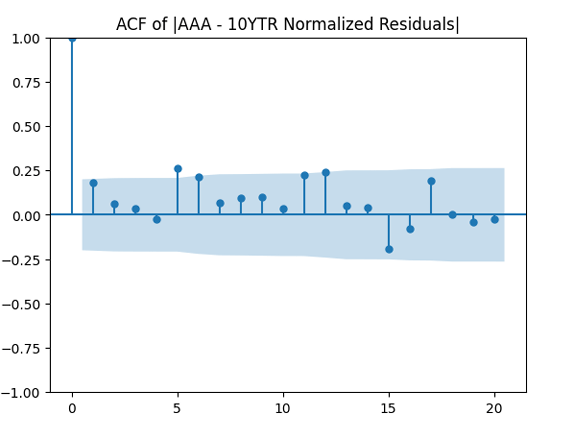

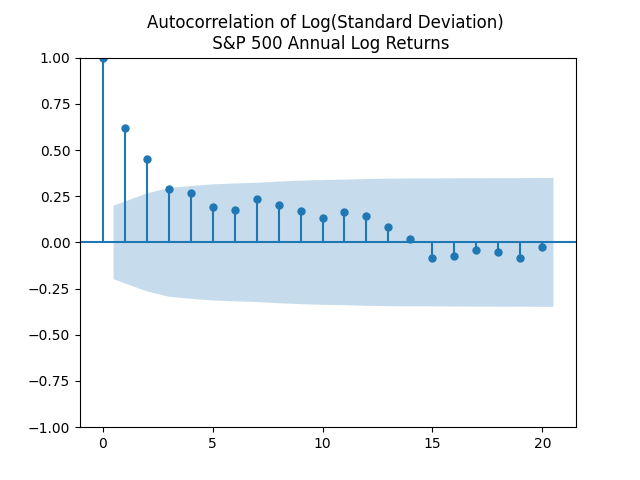

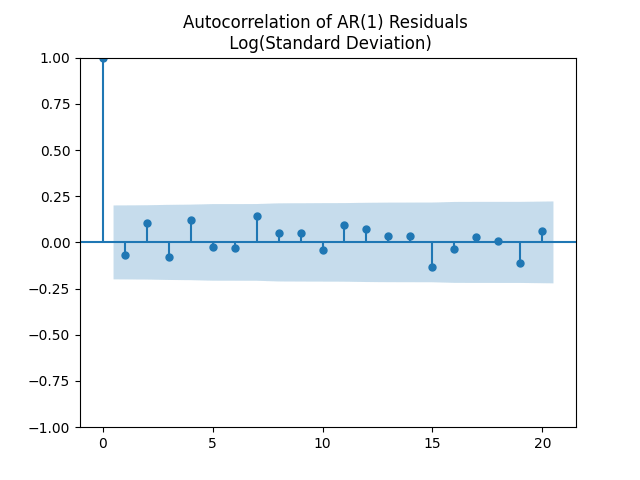

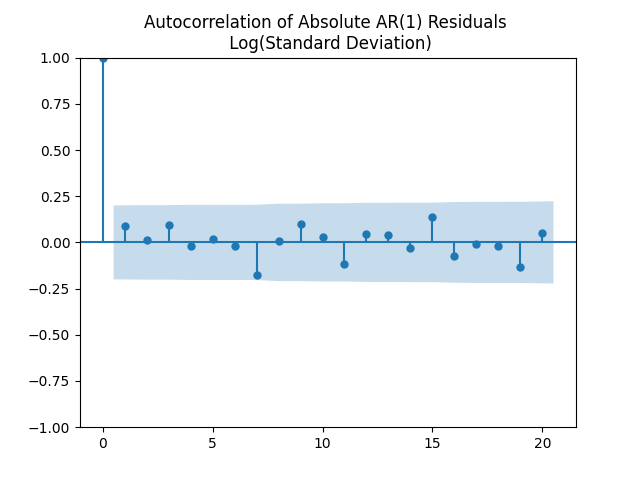

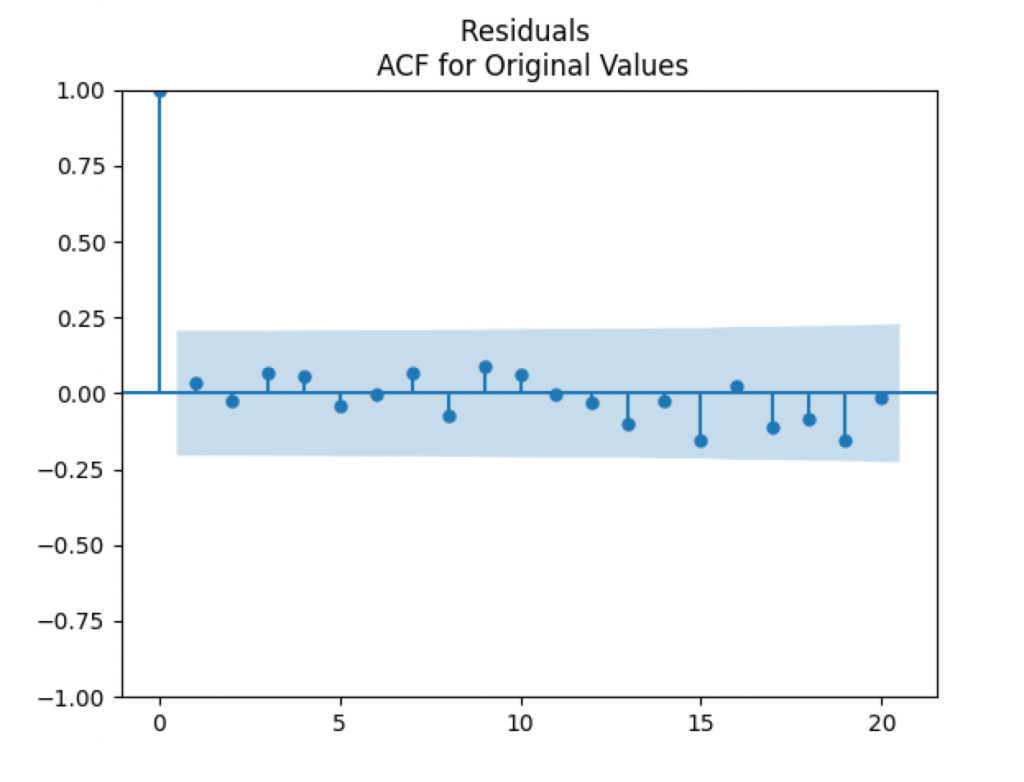

This is confirmed by the following quantile-quantile plot below. But the autocorrelation function plots for

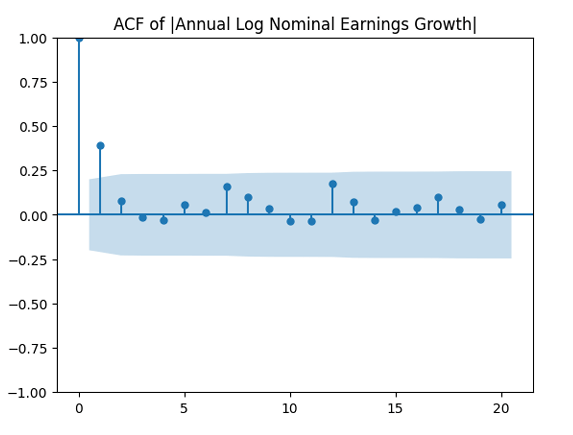

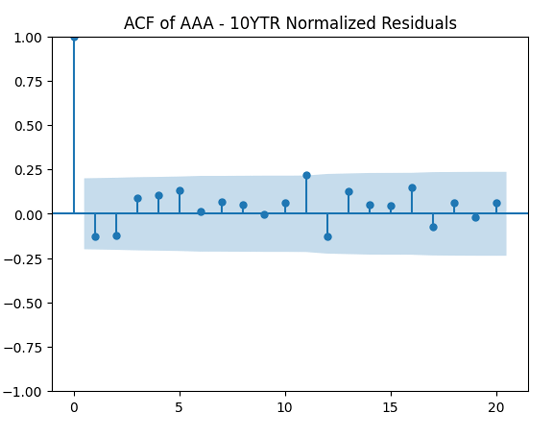

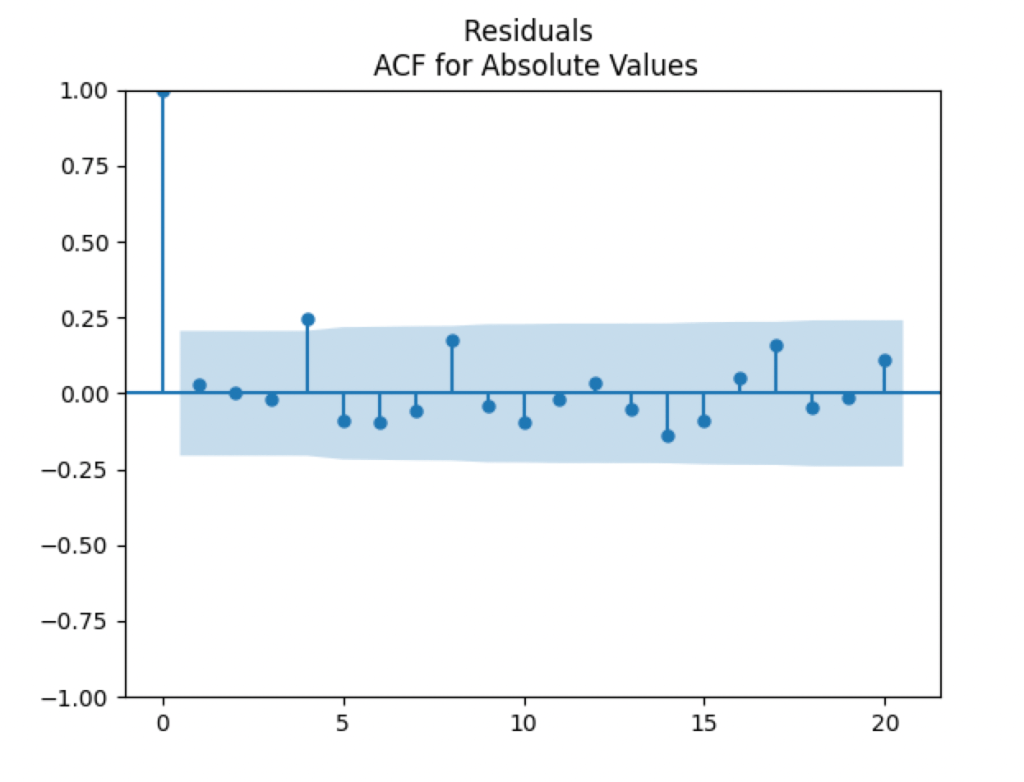

and for

below show that these are independent identically distributed.

This stays in contrast with our original research, when residuals (innovations) are independent identically distributed and Gaussian. Further research will include extending this to years 2024 and 1924-1928 when we have total returns and volatility data for shifted years.

The GitHub repository New Valuation Measure Replication contains code, data, and these graphs.