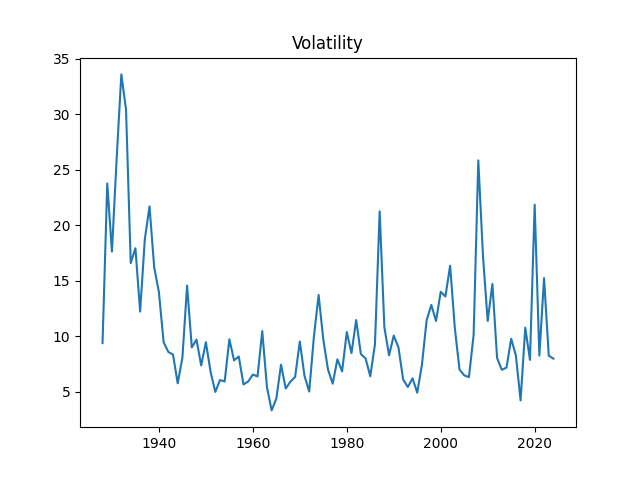

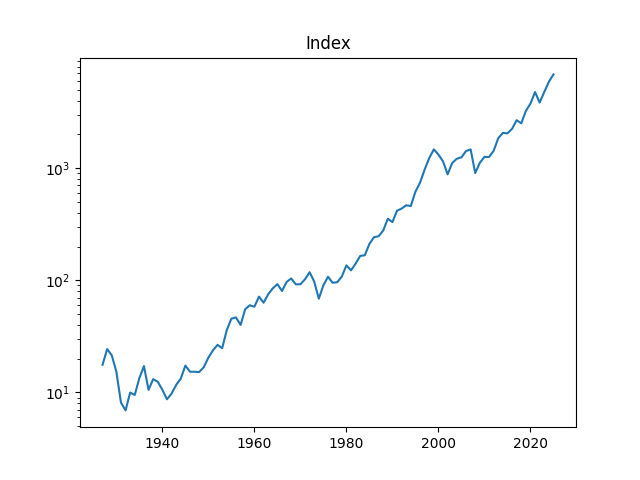

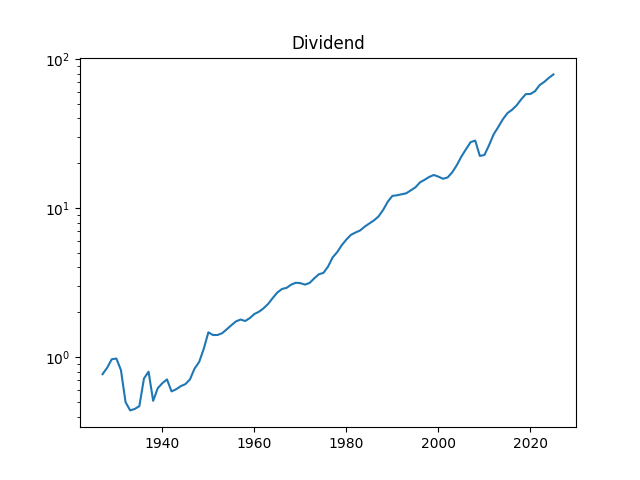

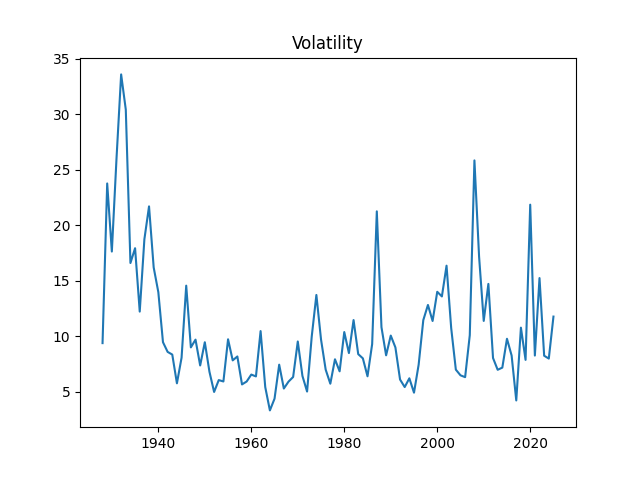

Dear readers, after a long break, I am back. I updated the annual volatility and other data for S&P 500 for the year 2025. Annual volatility is computed as the empirical standard deviation of daily log changes multiplied by 1000 (for normalizing). The end-of-year price for S&P 500 in 2025 is also updated. We also add S&P 500 dividends for 2025. Now we have data on volatility for 1928-2025, on dividends for 1927-2025, and end-of-year level of S&P 500 for 1927-2025 too.

We added the dividend data for 1927 as well, to increase the number of data points. This is fine, since S&P 90 (a predecessor for S&P 500) was created in 1926, and the data is taken from Robert Shiller’s data library.

The volatility for 2025 is 11.77. This is higher than the long-term average 10.51, or the 2024 volatility, which is 7.98. See the original post with computations of Angel Piotrowski for 1928-2023 and its previous update for 2024.

Dividends for 2025 are 78.92, which is significantly higher than dividends for 2024, which are 74.83.

The S&P 500 increased a lot in 2025: End-of-year 2024 level is 5881.63, but end-of-year 2025 level is 6845.5.

We could not yet provide earnings for 2025, since we have earnings for 2025 Quarter 4 reported only on 2026 Quarter 1, which is still ongoing. We will provide them as soon as we can.

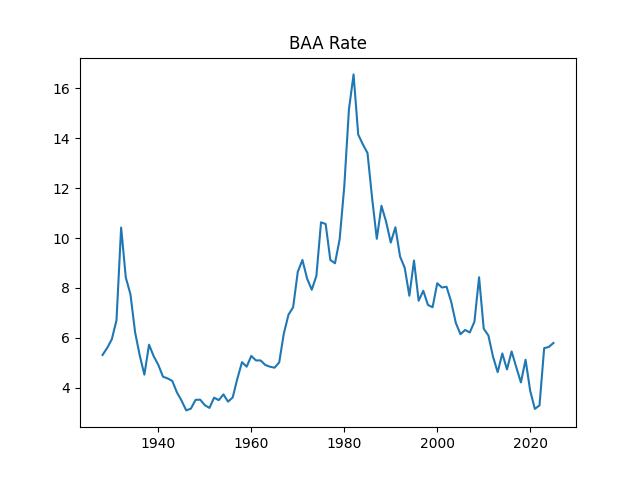

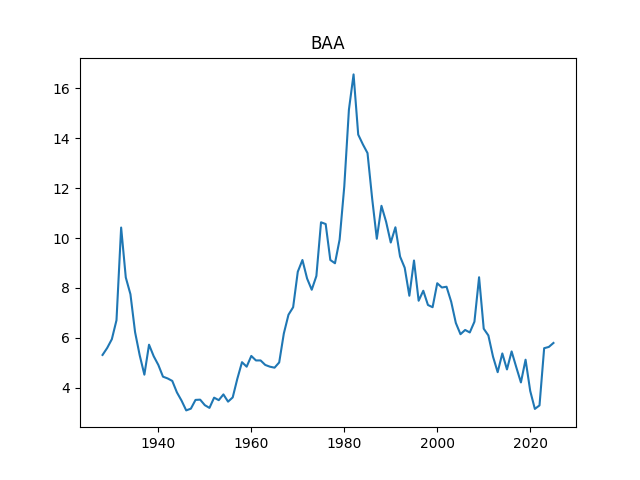

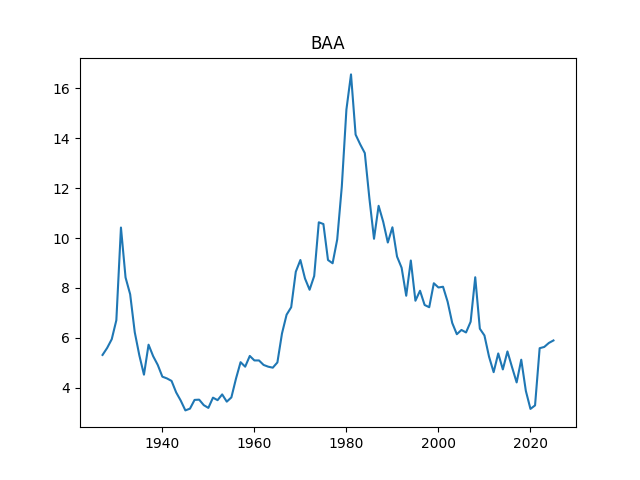

Finally, we added the BAA rate: December 2025 daily average. The BAA are lowest-rated investment-grade corporate bonds. The rate in December 2025 is 5.9, slightly higher than 5.8 for December 2024.

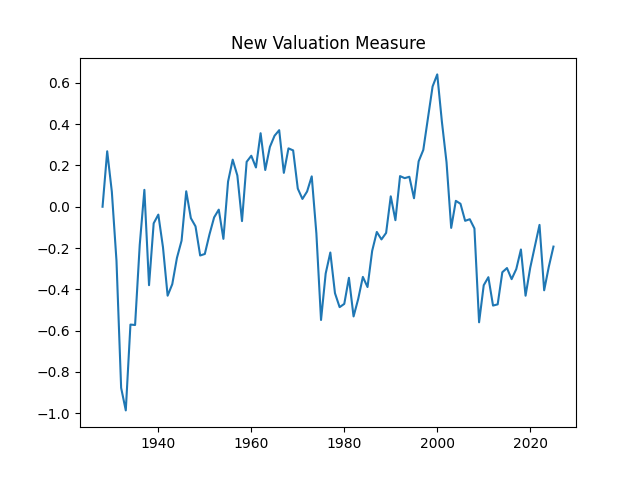

Above, logarithmic plots of index levels and dividends for 1927-2025. Below, the annual volatility and December BAA rate.

The data are published on my web page: We created a new tab named Financial Data Library on my web page. Let us now apply

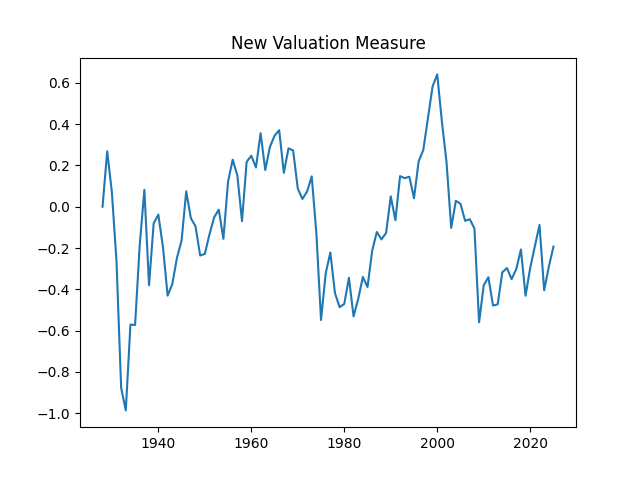

Let us replicate this post: Make stock returns IID Gaussian.

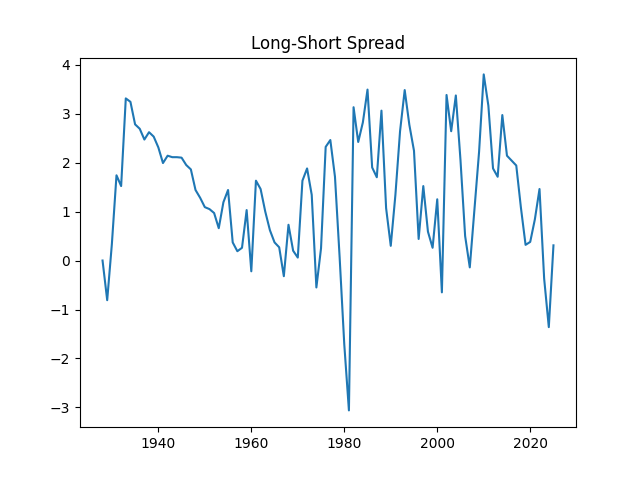

We have the following notation:

the S&P level at end-of-year

the dividend of S&P in year

December daily average BAA rate during year

annual realized volatility for the S&P for year

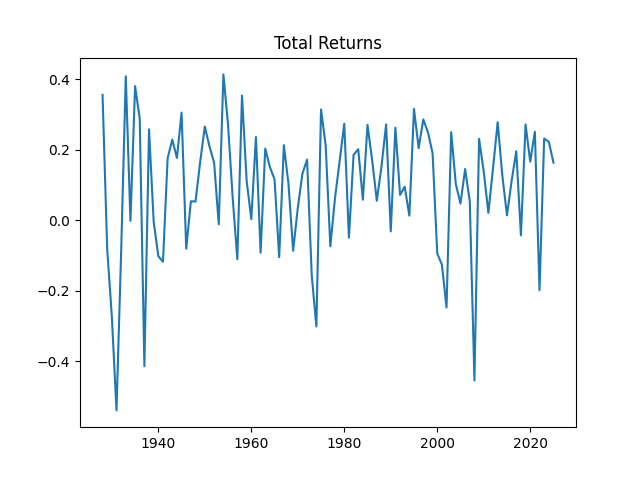

Compute total nominal geometric returns for the S&P 500: for year

Below is the graph of returns 1928-2025.

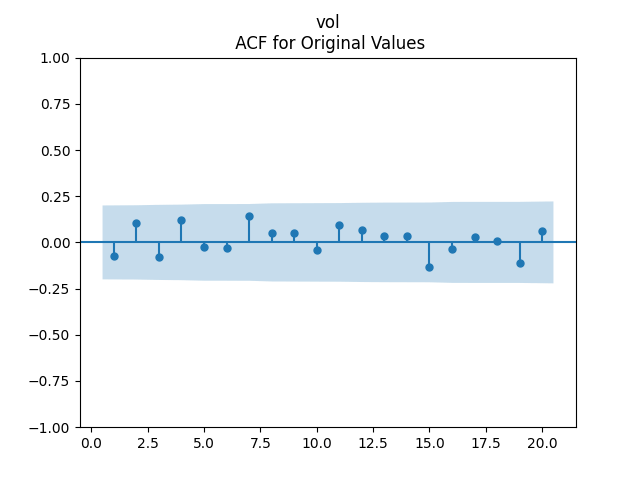

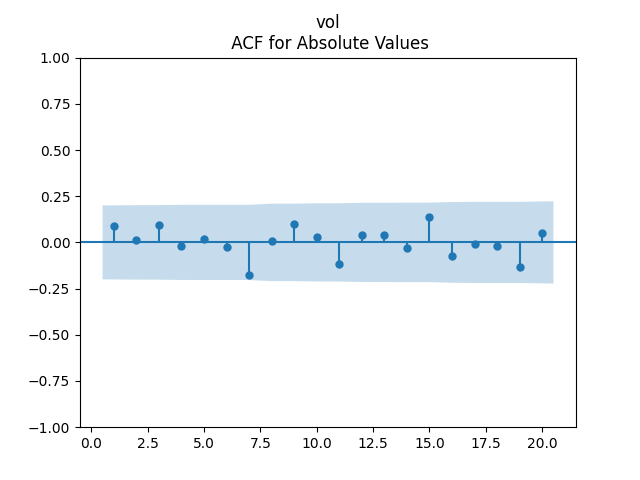

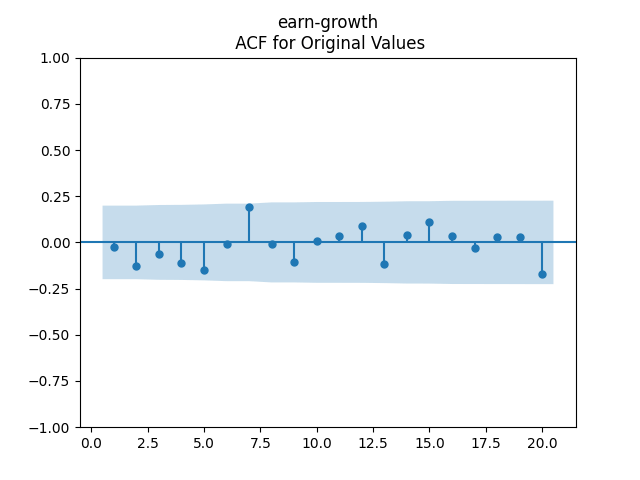

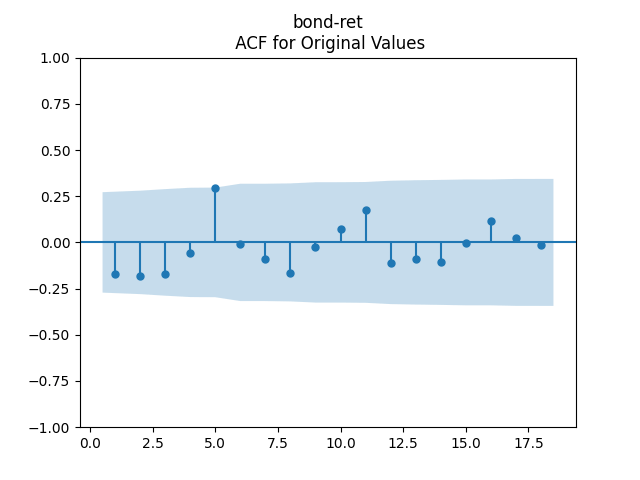

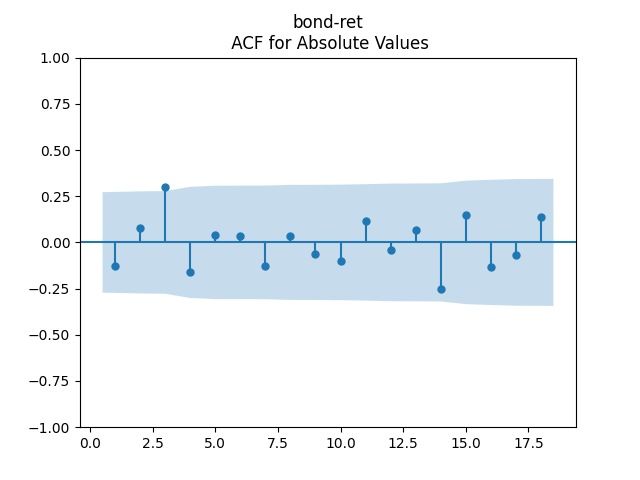

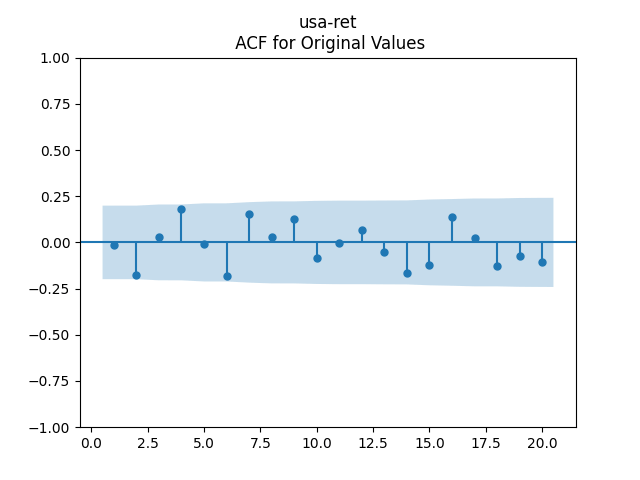

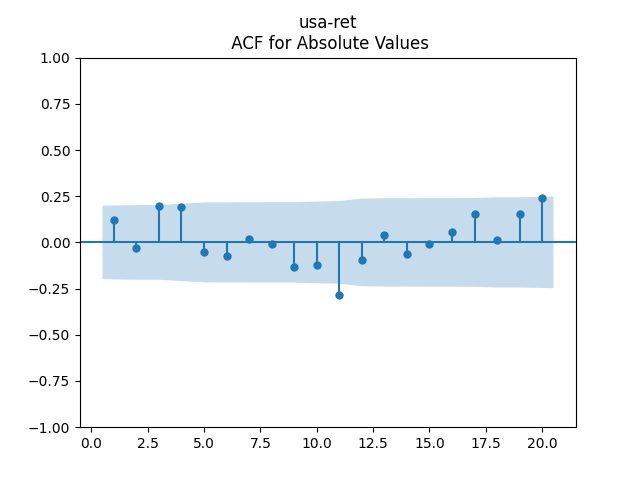

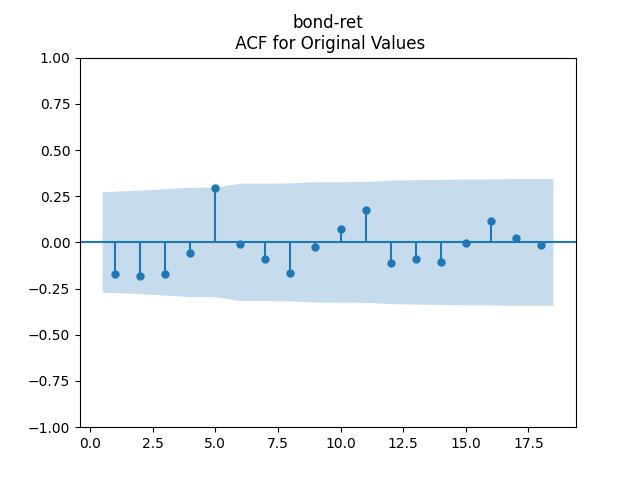

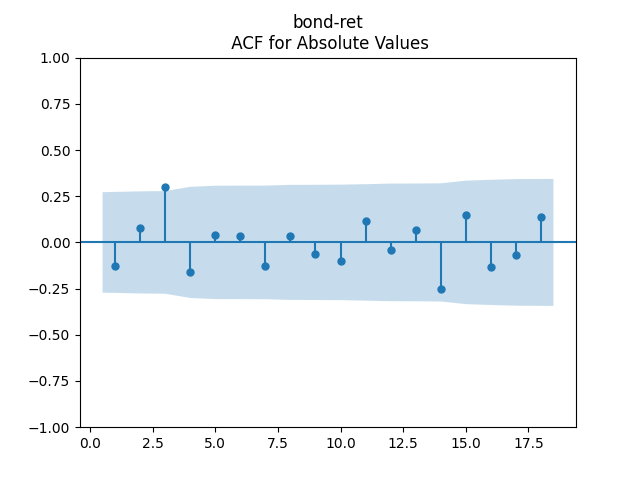

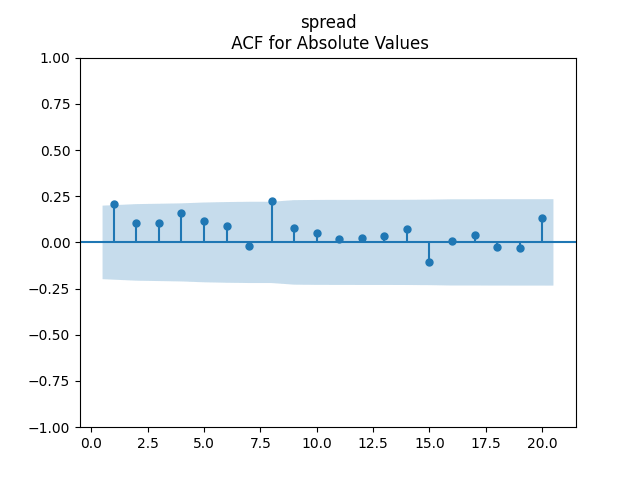

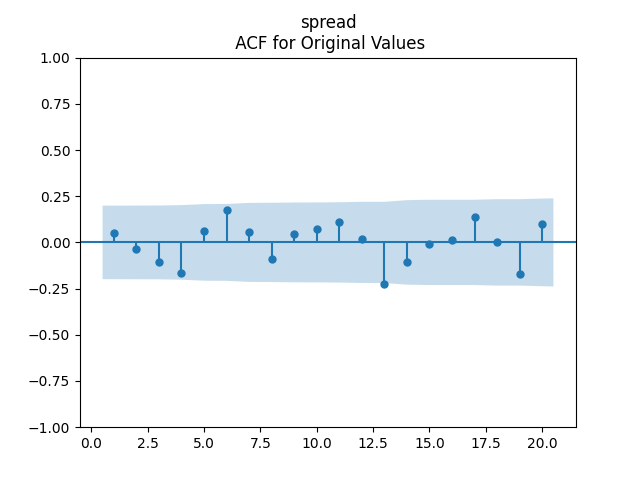

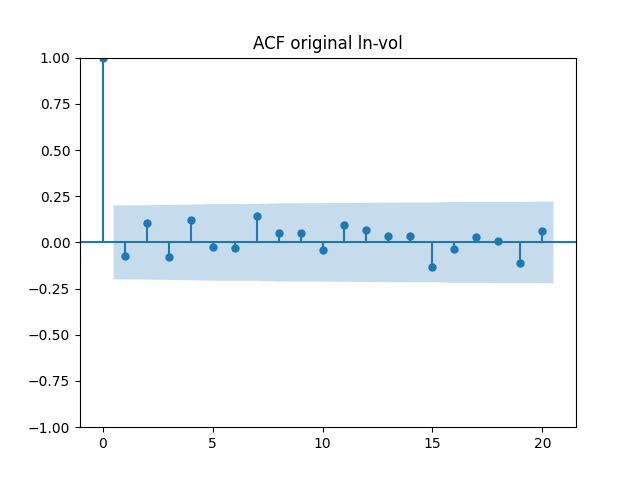

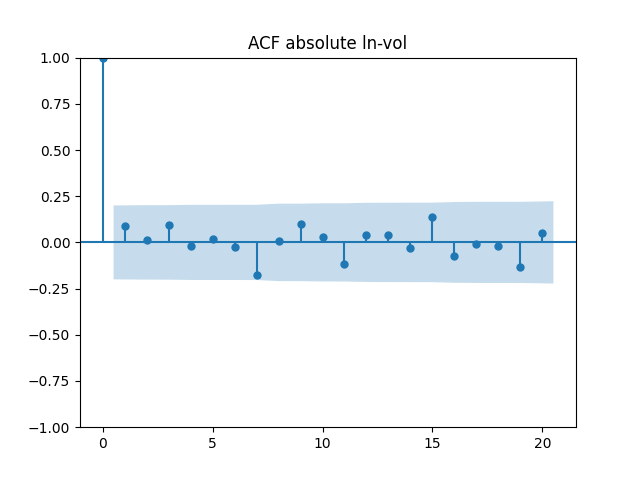

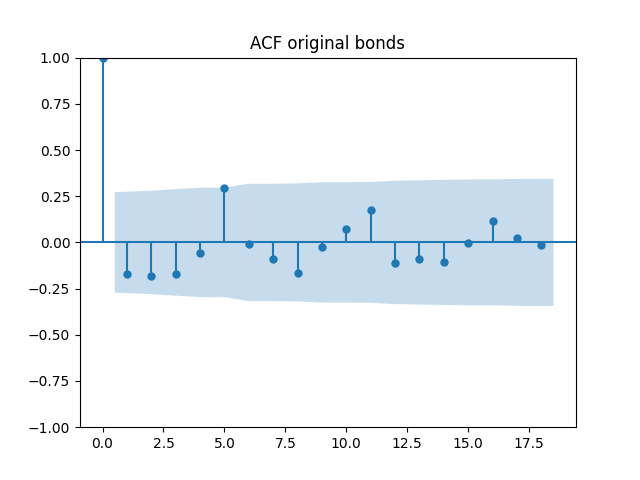

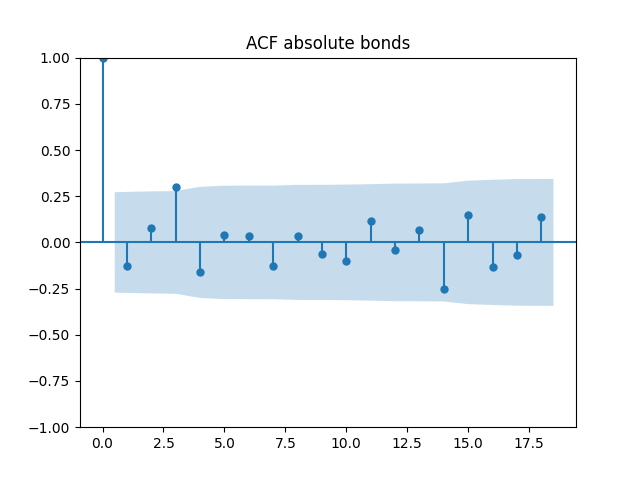

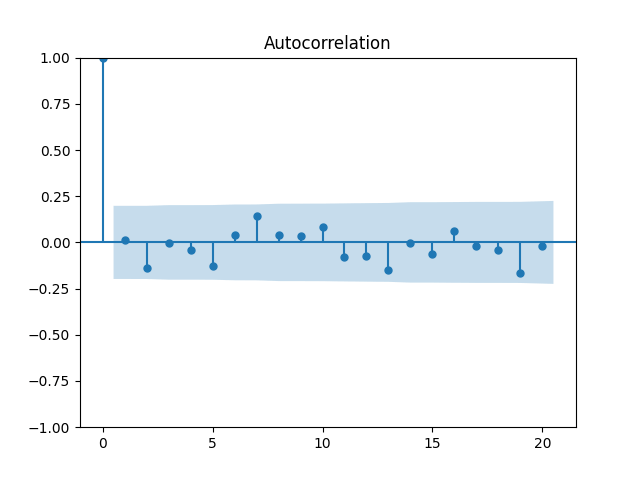

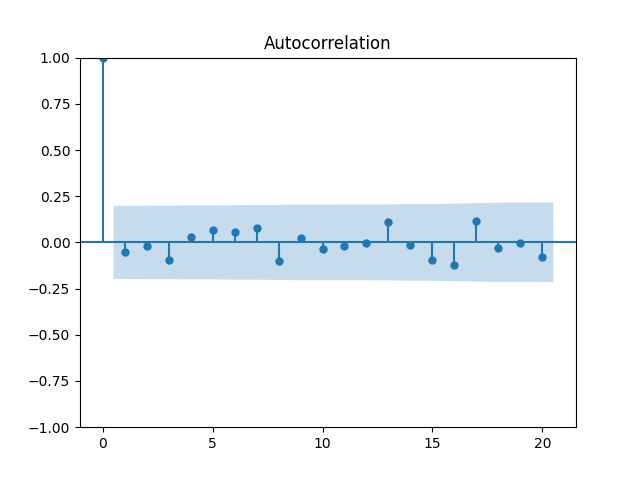

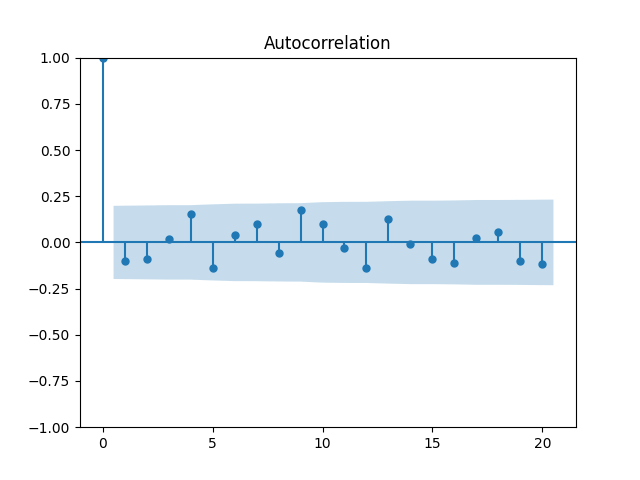

Now plot the autocorrelation function for these total returns And another autocorrelation function for their absolute values

Both plots are below, and both are consistent with the white noise hypothesis. It is surprising that we, in fact, do not have to divide total returns by annual volatility to make it white noise.

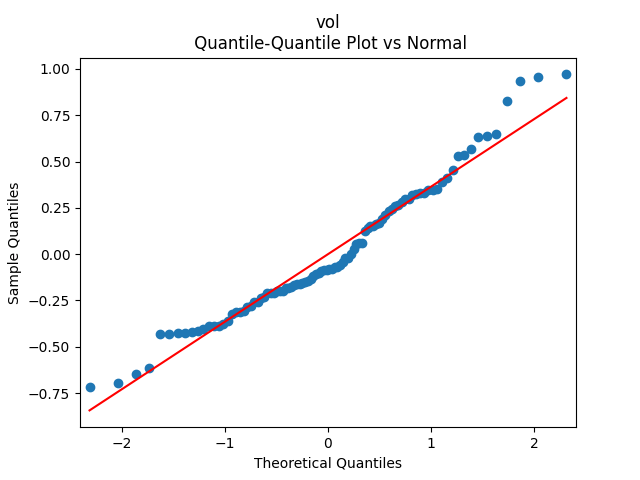

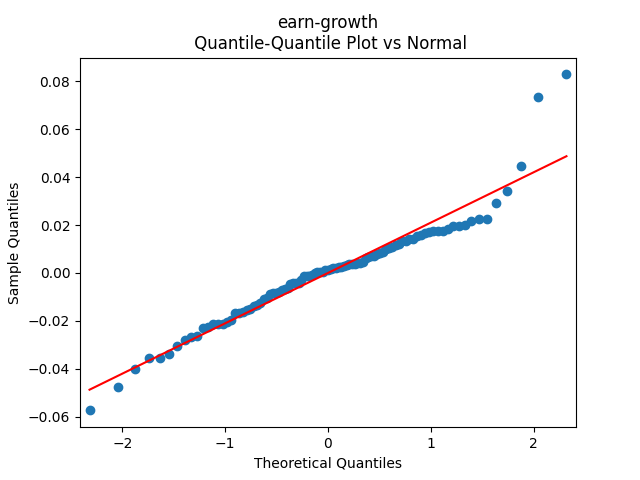

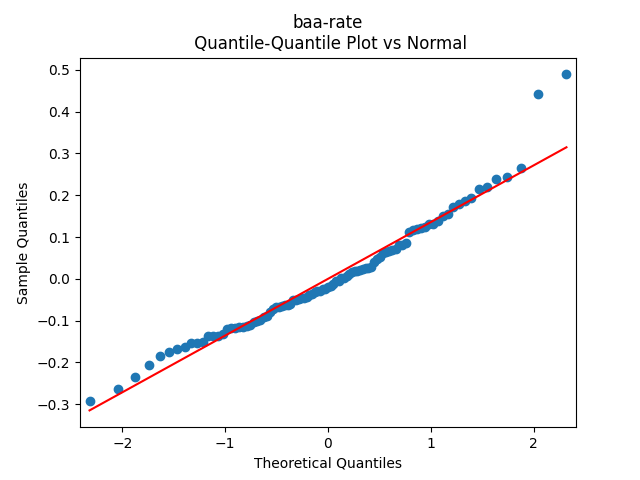

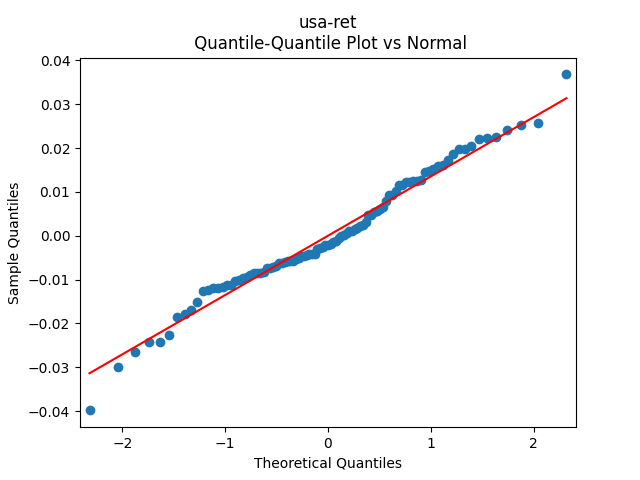

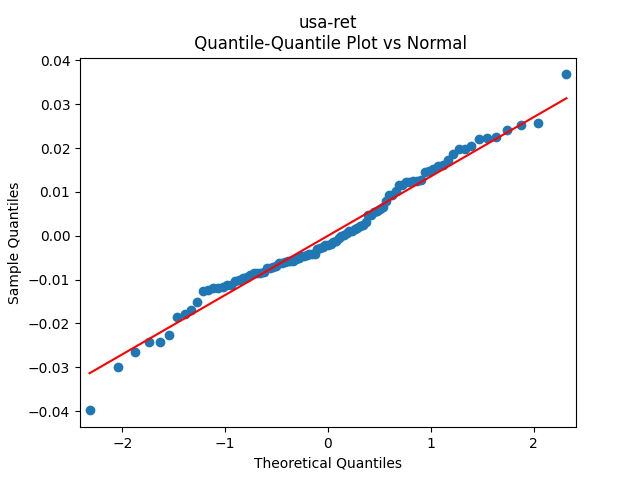

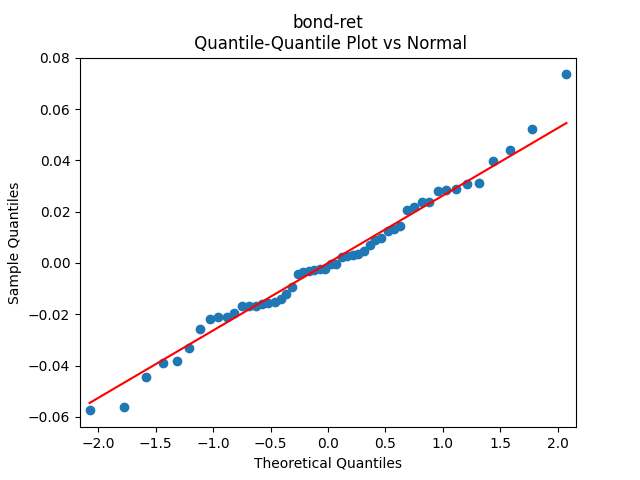

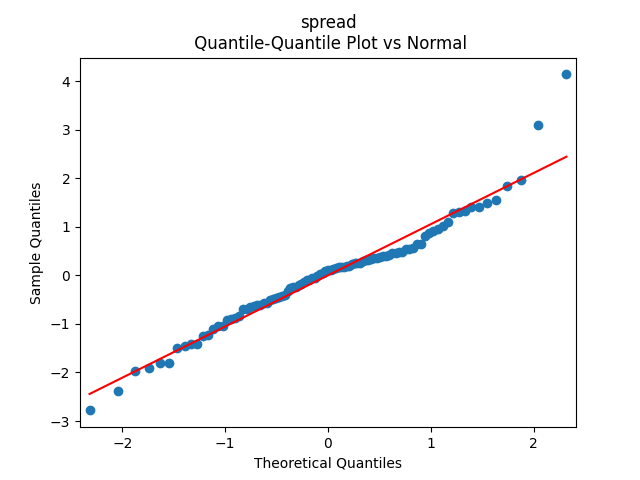

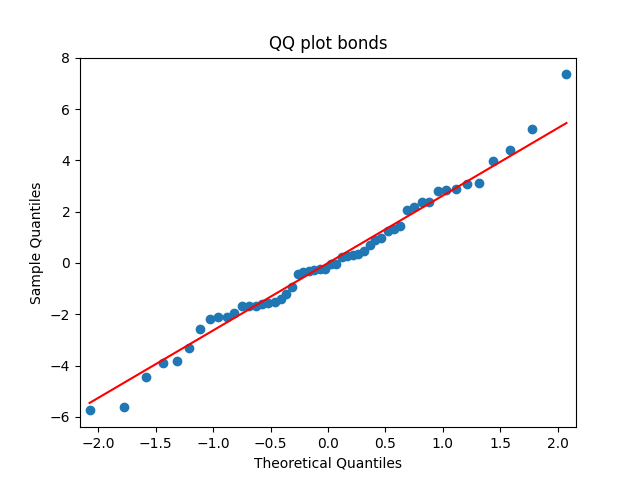

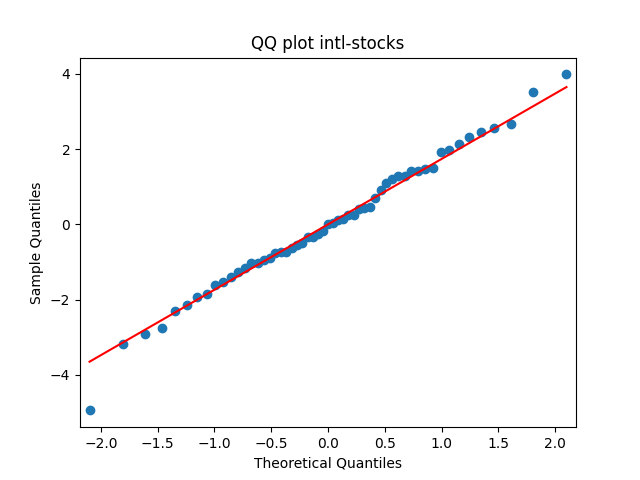

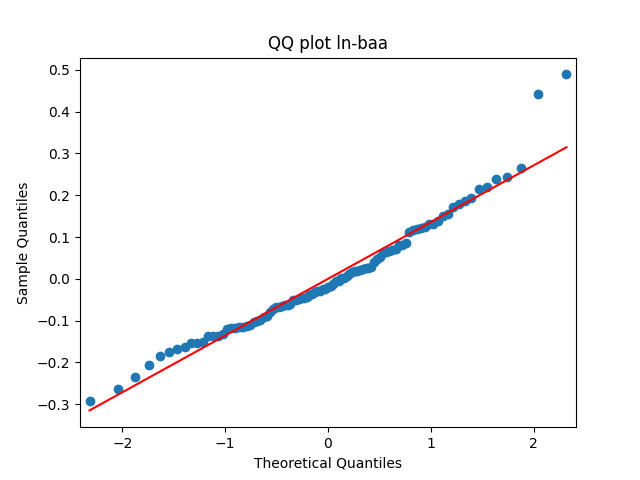

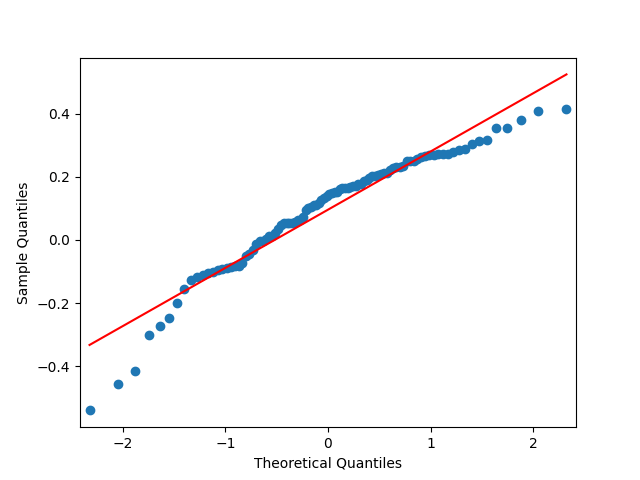

The quantile-quantile plot of these returns is shown below. We see that the returns are not Gaussian.

This is consistent with the normality testing. Shapiro-Wilk and Jarque-Bera tests give us and

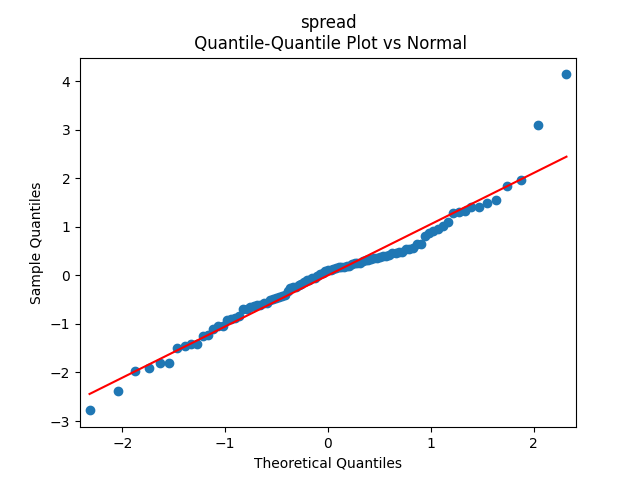

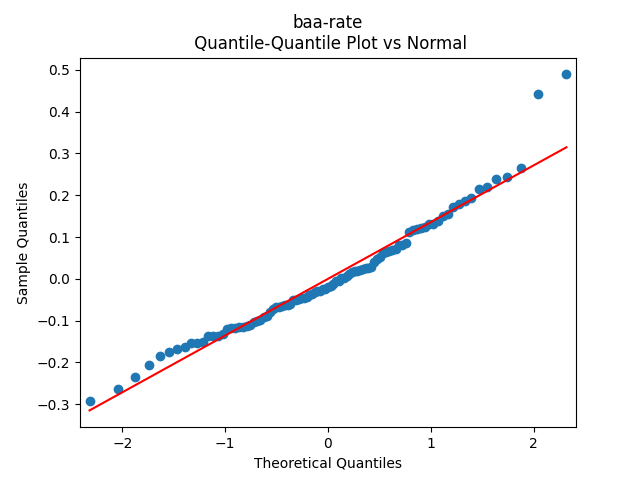

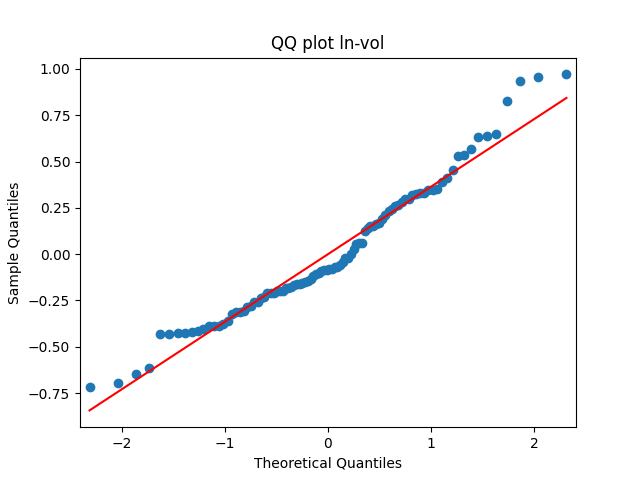

What if we do divide these total returns by annual volatility? We get

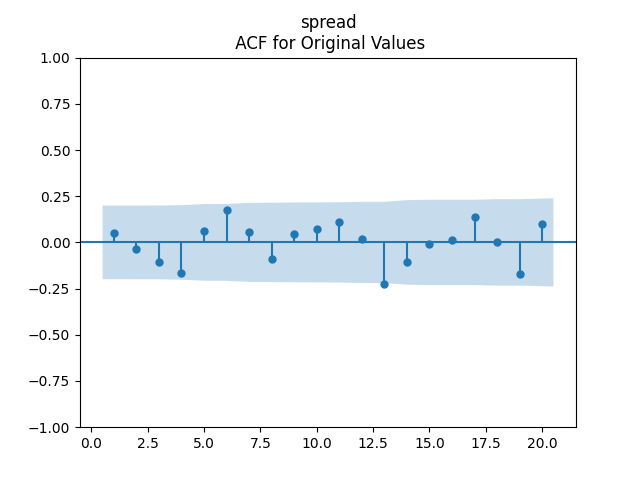

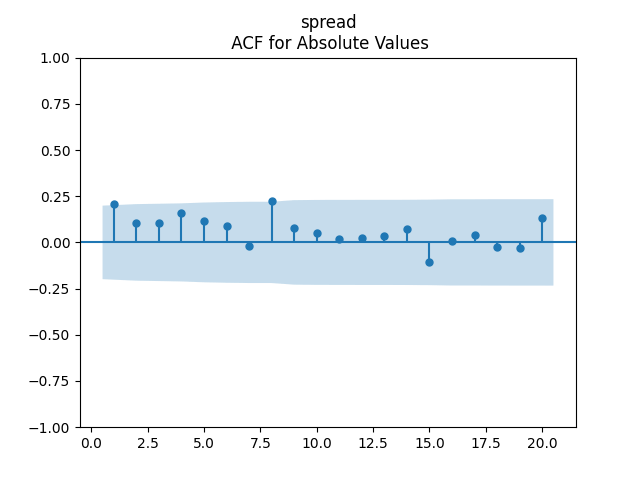

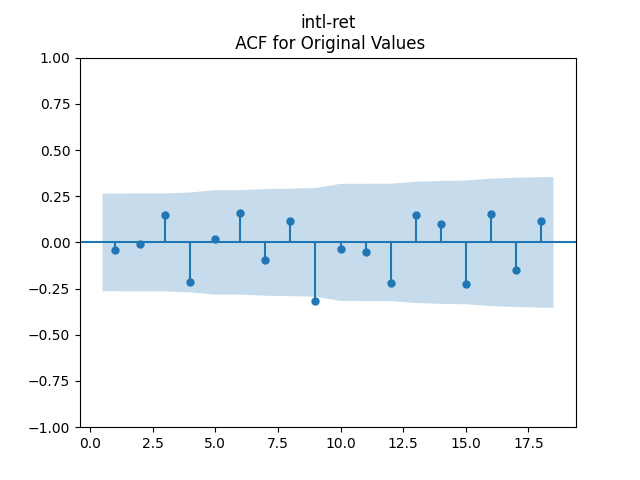

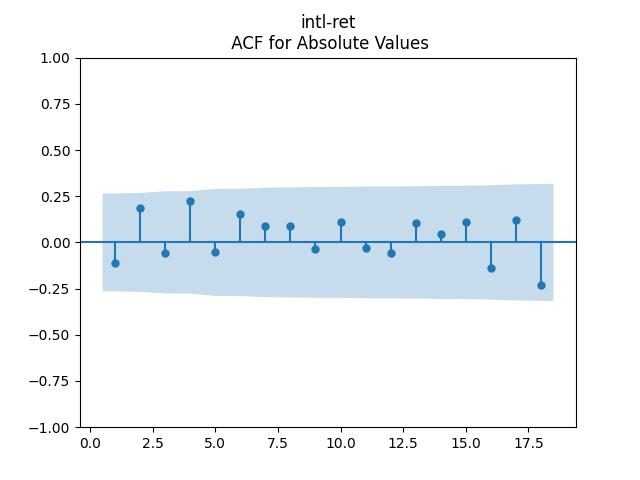

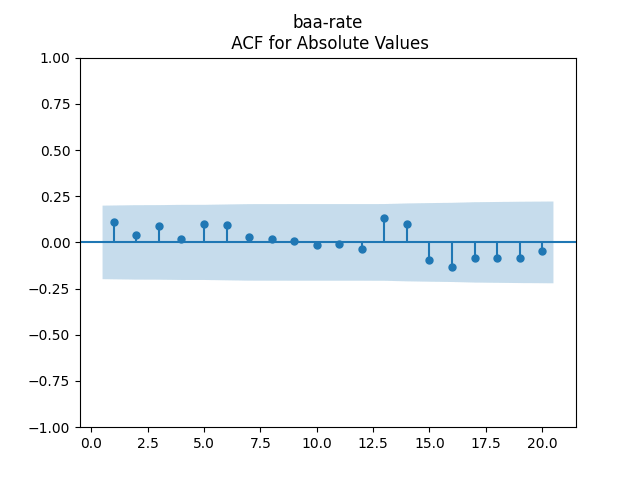

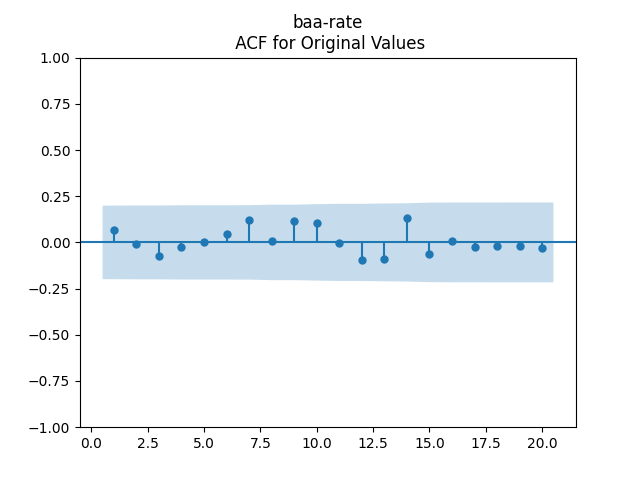

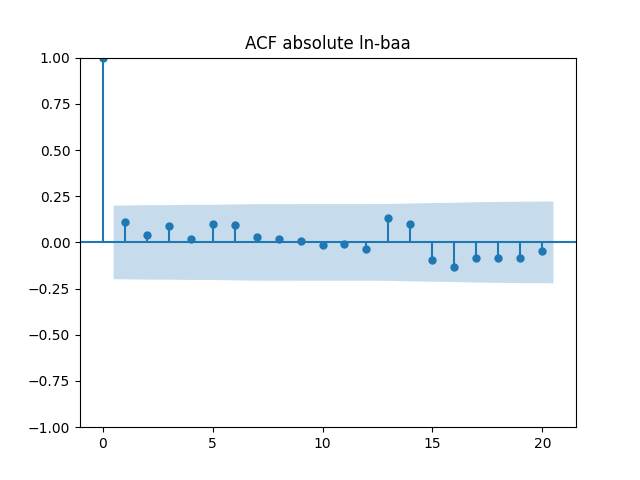

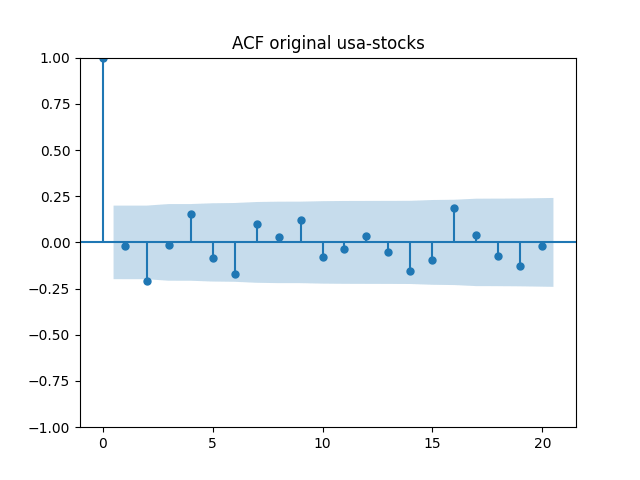

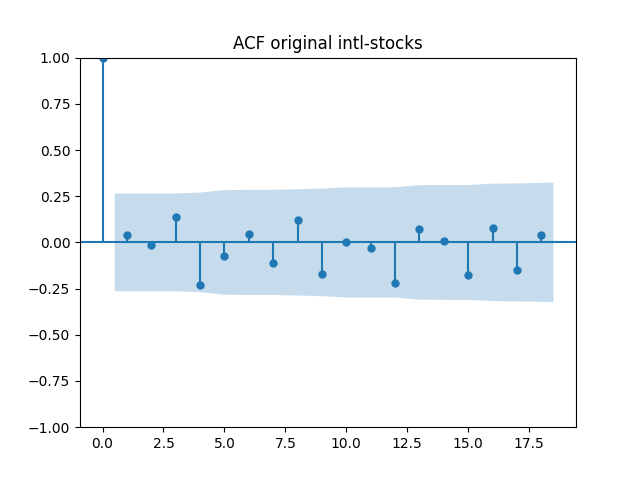

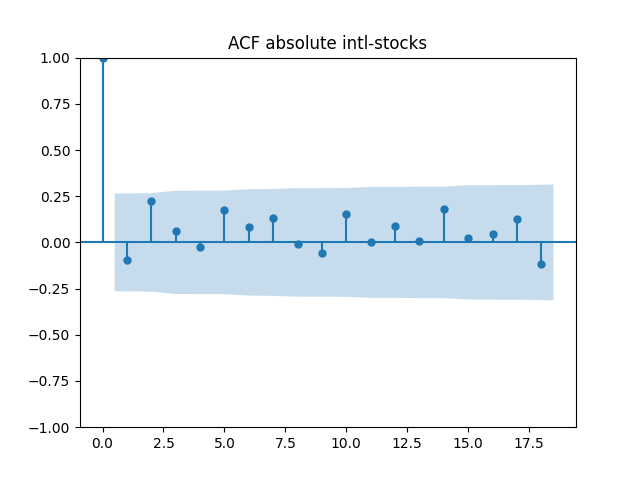

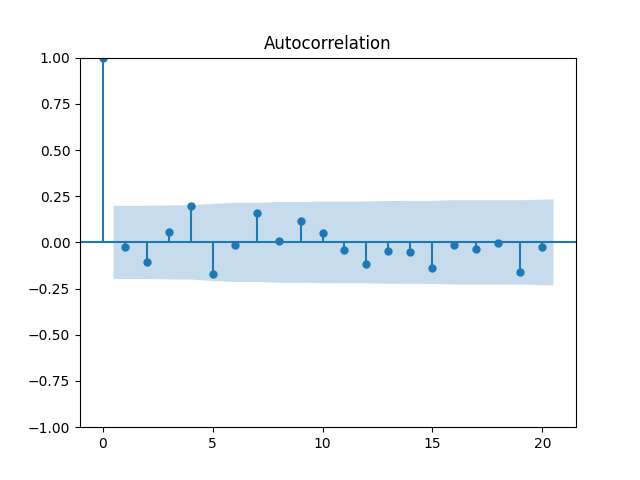

Let us plot the autocorrelation function for

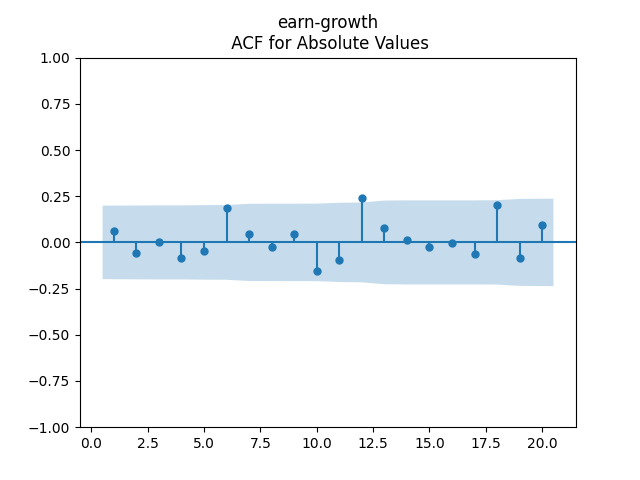

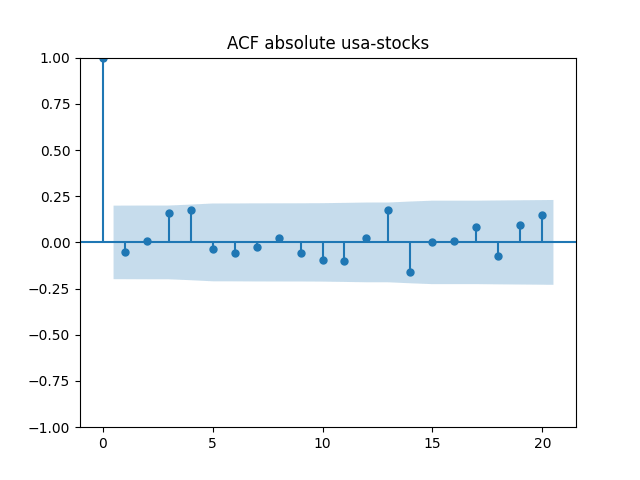

and the autocorrelation function for

These are still consistent with white noise, although, in my view, the autocorrelation function values are greater.