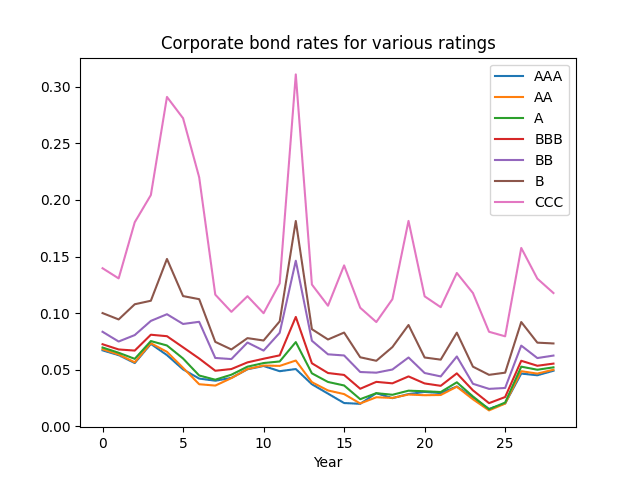

Here we use annual volatility to model bond rates: annual, end-of-year 1996-2024. We take Bank of America bond portfolios with the following seven rates: AAA, AA, A, BBB (investment-grade) and BB, B, CCC (junk, high-yield). Data and code are available on GitHub/asarantsev depository Annual-Bank-of-America-Rated-Bond-Data.

First, consider the rate on the last day of years 1996-2024. Below is the graph of them.

Let be this rate at end of year

Model as an autoregression:

And the results are available in the table below. The last three columns are: Autocorrelation function for innovations, sum of absolute values of the first 5 lags (ACFO); same but for absolute values of innovations (ACFA); Pearson test for

| Rate | Stdev of residuals | Skew | Kurtosis | Shapiro-Wilk | Jarque-Bera | ACFO | ACFA | Pearson Test | ||

| AAA | -0.21 | 0.0081 | 0.008 | 0.994 | 1.241 | 0.029 | 0.041 | 0.629 | 0.627 | 0.051 |

| AA | -0.23 | 0.0087 | 0.009 | 0.747 | 0.842 | 0.108 | 0.18 | 0.716 | 0.918 | 0.049 |

| A | -0.26 | 0.011 | 0.01 | 0.571 | 0.53 | 0.138 | 0.397 | 0.48 | 0.744 | 0.043 |

| BBB | -0.33 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.799 | 1.671 | 0.09 | 0.044 | 0.262 | 0.699 | 0.025 |

| BB | -0.46 | 0.031 | 0.02 | 1.479 | 3.951 | 0.007 | <0.001 | 0.482 | 0.814 | 0.009 |

| B | -0.57 | 0.048 | 0.026 | 1.612 | 3.629 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.366 | 0.727 | 0.003 |

| CCC | -0.57 | 0.082 | 0.055 | 1.338 | 2.051 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.576 | 0.626 | 0.004 |

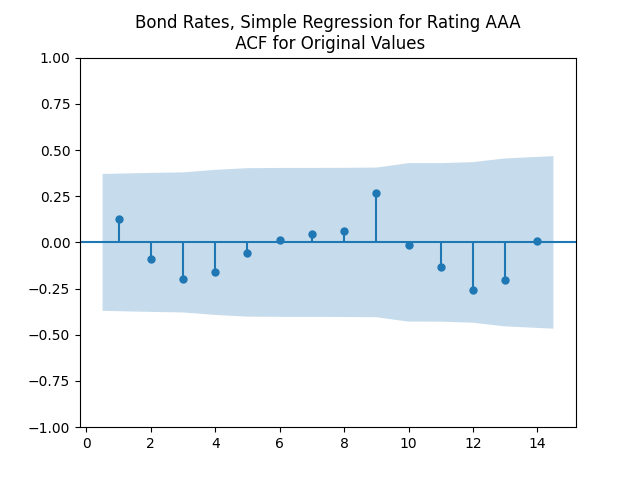

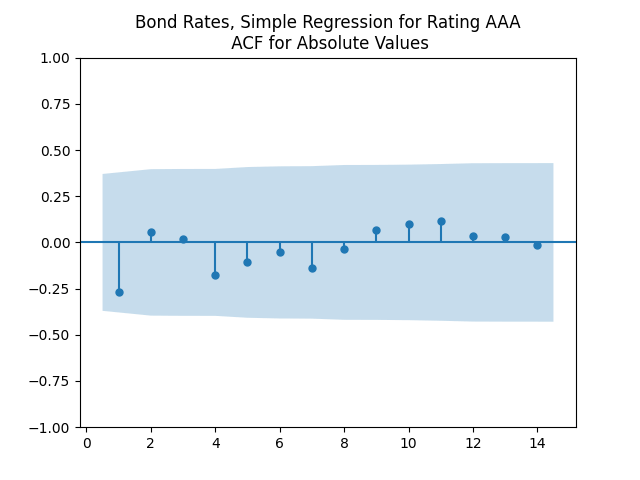

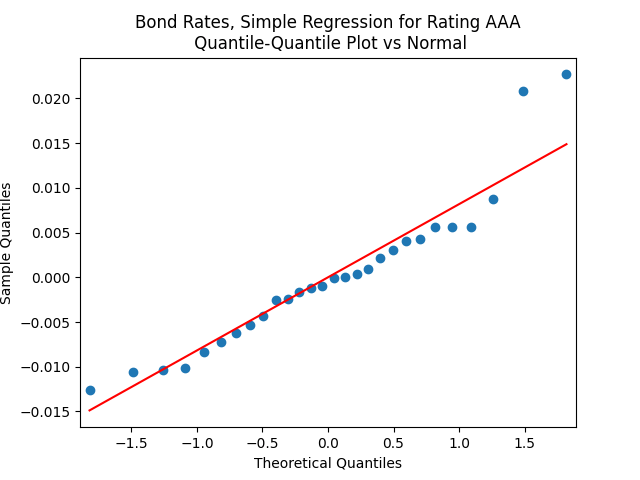

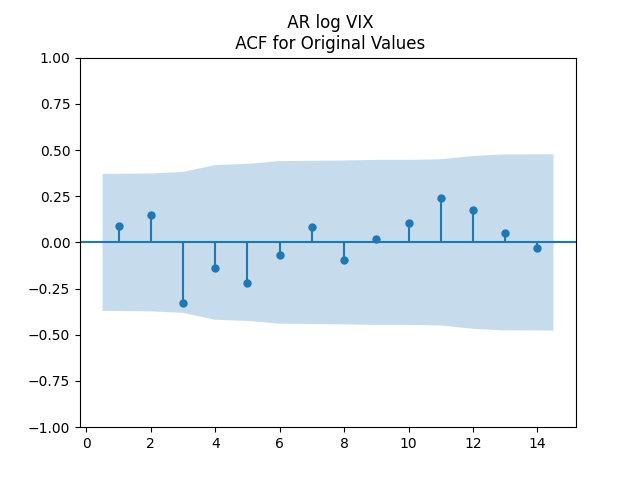

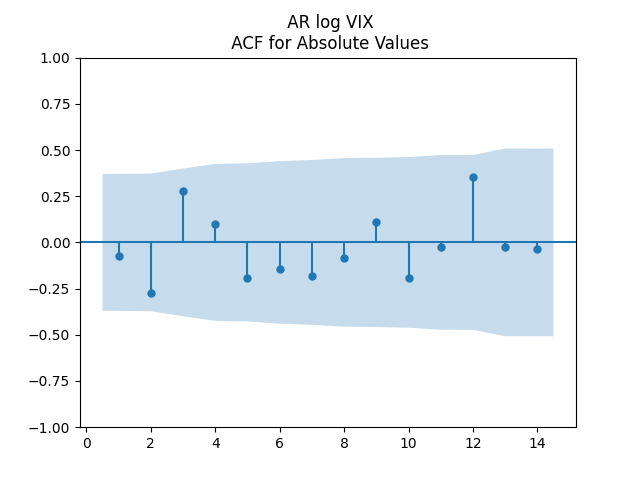

The autocorrelation function (ACF) plots for and for

shows that this is well explained by independent identically distributed random variables (white noise). But these are not necessarily normal, judging by the Shapiro-Wilk and Jarque-Bera normality tests. Especially for junk-rated bonds (BB, B, CCC) but also sometimes for investment-grade bonds. The random walk hypothesis could be rejected (using low

values) for all rates (even AAA is just barely above

). See also the plots below. We present only the plots for AAA, other ratings are similar. One can generate these graphs by running the code from the GitHub repository mentioned above.

As usual, we can improve fit and make innovations Gaussian by dividing them by annual volatility. Now we take average annual VIX instead of monthly. This parallels research by Angel Piotrowski mentioned in previous posts. But she computed annual realized volatility, and I use averaged VIX (implied volatility). Let us first fit the log Heston model for VIX 1996-2024:

Here, and

Next,

and

for Student

test for

The standard deviation for

is

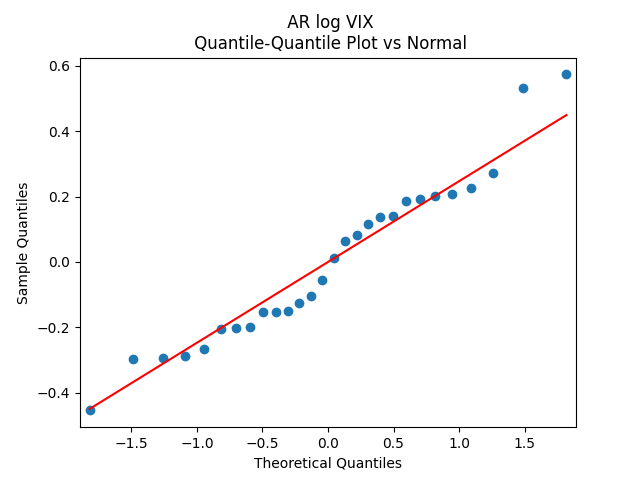

The normality tests for innovations

give us

for Shapiro-Wilk and

for Jarque-Bera. The plots for ACF of

and for

show independent identically distributed. See below. Thus the log volatility is indeed modeled by the autoregression of order 1, statistically significantly mean-reverting, with Gaussian innovations. This is similar to Angel Piotrowski’s research.

Consider the autoregression with normalization of innovations by dividing them by volatility

We have then

Divide by VIX and then get an ordinary least squares regression with residuals without intercepts. Let us add intercepts:

Results are available below in the table: Coefficients and analysis of innovations

| Rate | Stdev | Skew | Kurt | S-W | J-B | ACFO | ACFA | |||

| AAA | 0.01 | -0.14 | -2.41 | 0.00037 | 0.774 | 0.664 | 22% | 19% | 0.352 | 0.816 |

| AA | 0.0099 | -0.116 | -2.78 | 0.0004 | 0.67 | 0.807 | 43% | 24% | 0.402 | 0.924 |

| A | 0.0087 | -0.157 | -1.06 | 0.00044 | 0.342 | 0.2 | 93% | 74% | 0.395 | 0.963 |

| BBB | 0.0099 | -0.279 | -2.1 | 0.00051 | 0.039 | -0.4 | 96% | 91% | 0.405 | 0.779 |

| BB | 0.015 | -0.539 | 10.0 | 0.00076 | 0.303 | -0.21 | 88% | 79% | 0.656 | 0.594 |

| B | 0.0235 | -0.77 | 20.3 | 0.00096 | 0.35 | -0.126 | 46% | 74% | 0.576 | 0.722 |

| CCC | 0.0217 | -0.73 | 41.5 | 0.00198 | 0.58 | 0.25 | 36% | 44% | 0.817 | 0.948 |

All correlation between and

are not statistically significant. For investment-grade ratings, we have

higher than 5% for all coefficients. But for junk ratings,

for

And for the two bottom ratings,

for

Next,

for linear regression with

for most ratings is much higher than without it. So we need to include this term.

Thus we see a joint model: For and

we get:

IID

As discussed, we might consider to be the diagonal matrix, but might as well make it a complete matrix. This model fits very well. A disadvantage is that we have only ~30 years of data. We do need to normalize innovations of rates by dividing these by VIX. We do need the term

In our previous research, we proved long-term stability of this bivariate model. This is true not just for Gaussian innovations, but for more general cases, under certain conditions.

We continue this research in the next post, where we model total returns.

Leave a reply to Annual Corporate Bank of America Rates – My Finance Cancel reply