is it better to invest in stocks with zero or negative recent net income? The answer is no. Consider the monthly data from 1954 ( months). Compute total returns of negative earnings stocks and subtract risk-free returns (measured by 3-month Treasury rates), this is the equity premium

. Then do the same for the benchmark: top large

stocks, get

.

Simple linear regression with Capital Asset Pricing Model gives us , where

are residuals. Statistical tests show that W are close to independent identically distributed, but not quite Gaussian. The

. Here,

monthly (so

annually), thus excess return is negative. But

, so market exposure is much greater than 1! More risk, less reward!

A corroboration of value investing. This portfolio is capitalization-weighted: Each stock is weighted according to its market weight. This means we invest in a slice of the total market. Most index funds are capitalization-weighted. Rate data is from Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) web site, and stock data is from Kenneth French’s Data Library at Dartmouth College.

-

Stay Away From Negative Earnings

-

Market Volatility

A financial econometrician often hopes against hope that returns exhibit the following properties: (A) normal, following the bell curve; (B) IID, meaning independent identically distributed. Unfortunately, this is almost never true.

Here, let me describe a nifty trick: Dividing each data point by the standard deviation normalizes the data. The standard deviation of stock market returns (in financial econometrics this is called volatility) is not constant over time. Periods of economic calm and steady growth when volatility is small alternate with economic crises and financial crashes when volatility is large. It is not clear that dividing by overall volatility makes sense.

Another way to say is that volatility is stochastic: It is a random process by itself. How to extract this stochastic volatility, and how to model it? Here autoregressive conditional heteroscedastic (ARCH/GARCH) models are very useful. They model dependence of current volatility upon the past volatility and returns, with fixed number of lags. These are widely used in Quantitative Finance, often combined with classic linear autoregressive and moving average (ARMA) models. Every time series of returns would have

By chance, we discovered another trick, which obviates the need for GARCH-type models and allows to simply reduce all it to a couple of linear regressions. The miracle is that we can observe volatility independently and separately from the main time series!

Enter VIX, the index created and maintained by the Chicago Board of Options Exchange. Options are contracts which give the holder the right (but not the obligation) to buy or sell a stock or a stock index in the future (at a maturity) at a predetermined price (the strike). The celebrated Black-Scholes formula computes the option price based on current stock price, the strike price, the maturity, and the volatility.

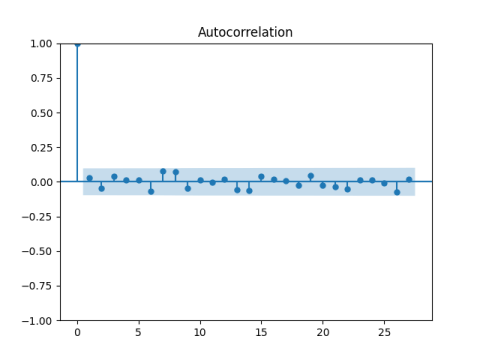

Lost of options are traded in Chicago based on S&P 500. Comparing the market price of each option at a given moment, we solve the Black-Scholes formula backward and find the unknown volatility. This is called the implied volatility. Taking a weighted average of all options, we get the overall implied volatility of the index, which is called VIX. It was computed daily for S&P 500 from the start of 1990, and for S&P 100 (a subset of S&P 500) from 1986.Below is the ACF plot. Take monthly returns of Wilshire Total Stock Market Index, including dividends, from 1990. Below is the plot of their autocorrelation (correlation between month

and month

, for each

) All correlations are very small and lie within a narrow blue band. This blue band is the fail-to-reject region, where you do not reject the null hypothesis that all returns are IID. It looks like this is, in fact, IID.

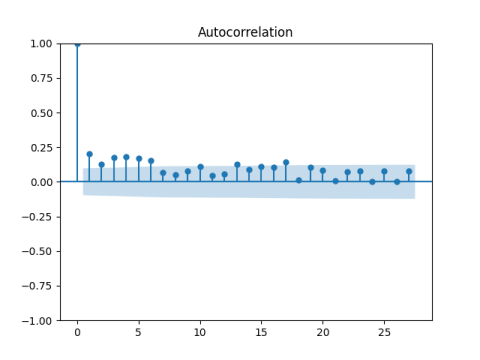

However, if we take autocorrelations for the absolute values, this is not IID anymore!

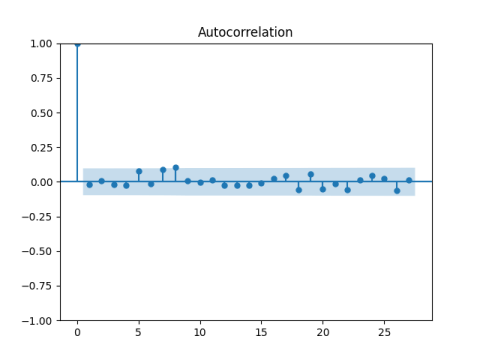

Finally, if we divide total returns by monthly average VIX, we get the autocorrelation functions for returns to be well-behaved, that is, corresponding to IID.

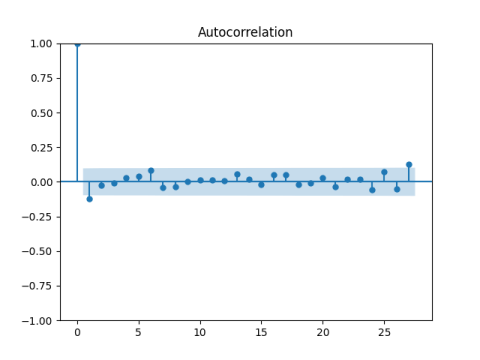

And for their absolute values as well.

We can have

without autocorrelation:

, but

with autocorrelation. In this case, plotting autocorrelation for

will give us a false impression that

is IID. This would be true if

were Gaussian, because for these uncorrelated means independent. Unfortunately, many times data in finance is NOT Gaussian, they have heavy tails!

We discussed in the last post the model, where

IID and

is auto regression or another mean-reverting process, independent of

. Then X have zero autocorrelation, but

have positive autocorrelation. Indeed, for crisis times V(t) is large and then

is large, and thus

and

are both large.

When analyzing financial and economic data, one should always be mindful of this possibility. If we checked autocorrelation for bothand

, and both are zero, then it makes sense to assume X are IID.

We can also apply white noise tests toand to

separately.

Consider correlations of; correlation of

; etc. correlation between

. Are they all close to zero? We can test them separately, or combine them (sum of absolute values, sum of squares, or another function = statistics). This gives us Box-Pierce, Ljung-Box, and any other white noise test.

Doing the same forinstead of

, we can reject or fail to reject white noise for

.

I created combined test (omnibus or portmanteau) to testand

simultaneously. See the article IID Time Series Testing (2023) in Theory of Stochastic Processes, published by the Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences.

Moreover, it makes them normal, or much closer to normal than originally! This is true by statistical tests of normality (Shapiro-Wilk, Jarque-Bera, or others) and by the quantile-quantile plot (QQ) vs the normal law.

Finally, these properties work for any well-diversified factor market portfolio: Small, Value, Large Growth, and so on. VIX was created from S&P 500 options, but it works for indices, portfolios, and funds other than S&P 500.

Of course, the mean, variance, and other statistics of normalized returns will be different for two different portfolios. But normality and independence stay.

Portfolios are many, but volatility is universal!

-

Arithmetic/Geometric Returns

Assume a stock cost 10$ on March 31, 2015, and 12$ on June 30, 2015. In addition, it paid dividend 0.5$ on June 12, 2015. Price return is computed as

R = 12/10 – 1 = 20%, and total return (including dividends) as Q = (12+0.5)/10 – 1 = 25%. These are arithmetic returns.

These are good for computing portfolio returns: For three stocks A, B, C, with total returns 10%, -5%, and 20%, consider the portfolio investing in them in proportions 40%, 30%, 30%. Then the total return of this portfolio is 0.4*10% + 0.3*(-5%) + 0.3*20% = 8.5%. Same is true if we are speaking of price return.

❌ However, compound interest presents a problem: If in January total return is 10% and in February it is 20%, then the overall total return is not 10% + 20% = 30%. Instead, it is 32%. Why? Because we get February return not simply on the original wealth but on the wealth gained in January. Indeed, if we start with wealth 100 on the New Year’s day then on January 31 we get 110 and on February 28, we get: 110*(1 + 20%) = 132, thus 100 turns into 132 which gives us 32%. Same problem if we got price returns instead of total returns.

Thus analysts sometimes use geometric (logarithmic) returns: Revisit the example at the beginning of this post. The price return is ln(12/10) = ln(1.2) = 18.2%, and the total return is ln(12.5/10) = ln(1.25) = 22.3%.

It is easy to convert arithmetic return into geometric return: If R is the arithmetic return, then G = ln(1+R) is the geometric return. Conversely, R = exp(G) – 1. But do not forget that percentages must always be converted to fractions, for example 0.05 instead of 5%.

This solves the compound interest problem: The total geometric return in January is ln(1 + 10%) = ln(1.1) = 9.5% and in February. Thus the overall total geometric return is 9.5% + 18.2% = 27.7% = ln(1+32%) = ln(1.32).

On the other hand, for geometric returns one cannot compute the portfolio return out of stock returns like we did for arithmetic returns. You need to convert it back to arithmetic returns.

Conclusion: Use geometric returns for analysis of financial time series, and arithmetic returns for portfolio analysis.

-

Welcome!

This is my short notices about financial econometrics and stochastic financial modeling. We discuss stocks, bonds, portfolios, rates, volatility, and more. WordPress was chosen because it supports

. I am a professor of Mathematics & Statistics at the University of Nevada, Reno.